As of today, Experiments in Manga is now five years old! In some ways it feels like I’ve been writing here forever, and in other ways it seems like I’ve just started. When I first began Experiments in Manga, I had no idea how long it was going to last (honestly, I still don’t know), but I am rather pleased that I’ve been able to keep it going for so many years. And I find it especially impressive when I stop to consider all of the other things going on in my life right now.

What are some of those other things, exactly? Well, I and my partners all managed to survive our first year of parenthood, for one. (As did the little one, whose first birthday was last week.) That has certainly been a huge change in my life. I’m incredibly busy at work of late, too, since my supervisor retired in December and I’m still filling in for that position on top of my regular one. Another significant development is that I am now part of the leadership team for a new taiko performance group and I’ve more or less become an alternate for another semi-pro ensemble. I’ve actually been doing some teaching and composing for taiko, too. It’s all been rather exciting. And extremely challenging. And a bit exhausting.

There really doesn’t seem to be such a thing as “free time” anymore for me, and since Experiments in Manga is something that I do in my free time… Well, this past year is the first year that I’ve posted fewer things than I did in the year immediately preceding. Although I have been able to maintain a regular schedule, overall I’m reading less, and I’m writing less, too. I miss both things terribly (the reading especially), but I might have to cut back even more in the coming year depending on how things continue to progress and for the sake of my own sanity.

For example, I’ve decided to quietly retire the Discovering Manga and Finding Manga features. I enjoyed writing them, but I’m just not posting them frequently or regularly enough. (Which I then end up feeling guilty about.) But although I may be saying goodbye to those particular features, last year I actually introduced a new one that seems to be rather popular: Adaptation Adventures. I’ve only posted two so far—Udon Entertainment’s Manga Classics (which incidentally was one of my top posts from the last year) and The Twelve Kingdoms—but I’m hoping and looking forward to writing more.

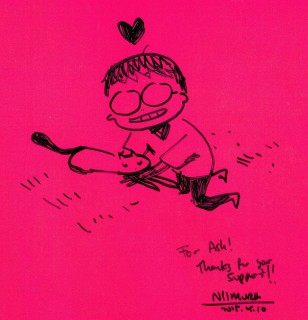

Speaking of top posts, my Spotlight on Masaichi Mukaide was very well received. In fact, it wasn’t just one of the top posts from last year, it’s one of Experiments in Manga’s most frequently visited pages ever. It probably helped that the spotlight made the rounds on general comics sites in addition to catching the attention of manga enthusiasts. That single post may very well be the most noteworthy thing that I’ve ever written. Likely, I’ll never be able to top it. I’dbe lying if I tried to say that I wasn’t at least a little proud of it.

The most popular (or at least most frequently viewed) manga reviews at Experiments in Manga from the last year included the anthology Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make It, Aki’s The Angel of Elhamburg, Mentaiko Itto’s Priapus, Aya Kanno’s Requiem of the Rose King, Volume 1, and Yaya Sakuragi’s Hide and Seek, Volume 1. (On a personal note, I am rather pleased that all five of those manga to one degree or another have a queer bent to them.)

As for my top non-manga reviews from the past year there was The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan by Ivan Morris, Haikasoru’s anthology Phantasm Japan: Fantasies Light and Dark from and about Japan, Frederik L. Schodt’s Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics, Seven Seas’ edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll with illustrations by Kriss Sison, and Yu Godai’s Quantum Devil Saga: Avatar Tuner, Volume 1.

I’m actually pretty happy to see Avatar Tuner on that list; the novel was one of the books published in 2014 that left the greatest impression on me. As was Massive, for that matter. Last year was actually only the second time that I compiled a list of notable manga, comics, and prose, but I’ll likely compile another one for 2015 since I had so much fun putting together the first two. Plus, other people seem to enjoy them. That goes for my TCAF posts, too, which remain popular. As long as I attend TCAF, and as long as I’m still writing at Experiments in Manga, I plan on rounding up my experiences at the festival.

Another feature of sorts that I’ve continued to work on is my monthly manga review project—a recurring set of reviews that focuses on a specific series or genre. In November, I wrapped up my second project, “Year of Yuri”, a series of reviews featuring manga and comics with lesbian themes. For the following review project, I was feeling in the mood for some horror manga. But while I picked the genre, I let readers of Experiments in manga pick the series. It ended up being a tie between Setona Mizushiro’s After School Nightmare and Yuki Urushibara’s Mushishi, so I decided to review both series, alternating between them each month. At the moment, I’m about halfway through the project.

I still maintain that I write Experiments in Manga for myself, but it does give me great satisfaction and joy to know that other people read and appreciate it as well. Over the last year several readers have let me know that they’ve given a particular manga, comic, or novel a try simply because I wrote about it. I and Experiments in Manga have started to be referenced and cited in Wikipedia as well as other places online as well, including an Italian comics website. (Admittedly, while very cool, I also find this kind of terrifying.) As always, I would like to thank everyone out there who reads and supports my efforts here at Experiments in Manga. It’s truly appreciated. I hope that I can continue to improve and continue to provide content that is useful or at least occasionally interesting. Here’s to another year!