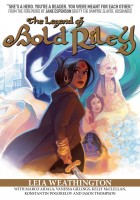

Creator: Leia Weathington

Creator: Leia Weathington

Illustrator: Vanessa Gillings, Jason Thompson, Marco Aidala, Konstantin Pogorelov, and Kelly McClellan; Chloe Dalquist and Liz Conley

Publisher: Northwest Press

ISBN: 9780984594054

Released: June 2012

The Legend of Bold Riley is writer and illustrator Leia Weathington’s first graphic novel. Published by Northwest Press in 2012, the volume is a collection of related stories, each illustrated by a different artist. In addition to Weathington, Vanessa Gillings, Jason Thompson, Marco Aidala, Konstantin Pogorelov, and Kelly McClellan contributed their artistic skills to The Legend of Bold Riley, with Chloe Dalquist and Liz Conley assisting with some of the colors. I first became aware of The Legend of Bold Riley thanks to the involvement of Thompson (to whom I give partial credit for igniting my interest in manga). And it’s thanks to The Legend of Bold Riley that I discovered Northwest Press, a publisher specializing in queer comics, graphic novels, and anthologies. The Legend of Bold Riley is a sword and sorcery adventure featuring a princess as a hero. She also happens to be a lover of women. Happily, The Legend of Bold Riley doesn’t end with this collection. The second volume, Unspun is currently being serialized and Weathington has already started working on a third book.

Rilavashana SanParite, who would come to be known as Bold Riley, is the youngest child of the king and queen of the eastern nation of Prakkalore. She and her two older brothers are heirs to the throne, groomed to be fair and just rulers of the kingdom and knowledgeable in the arts of state in addition to the fine arts, sciences, history, and swordplay. But Riley finds that her heart lies somewhere beyond the walls of the capital city of Ankahla and even beyond the borders of Prakkalore. She wants to travel the world to see the places and meet the people she’s only ever read about in her studies. And so the princess sets out with a sword strapped to her side and a horse to carry her, first to the southern kingdom of Connchenn and then further to the jungles of Ang-Warr, the distant Qeifen, and all the lands in between. Over the course of her journey Riley meets gods and battles demons, the sharpness of her mind and wits just as valuable as the sharpness of her sword. She even falls into the bed of a lovely lady or two.

Although the stories in The Legend of Bold Riley all have continuity with one another, the prologue and the five individual chapters that follow can largely stand on their own once Riley has been introduced. As already mentioned, each chapter is illustrated by a different artist. Riley is always recognizable, but otherwise there is no attempt to have uniform artwork in the volume. Instead, the artists are given free rein, resulting in a marvelous assortment of different art styles and illustration techniques and a range of color palettes. The resulting shift of mood and atmosphere is quite effective in emphasizing the changes in the setting and the type of story being told from one chapter to the next. As Riley travels, visiting different countries and kingdoms, the artwork reflects those differences. The Legend of Bold Riley is diverse, and not just in its illustrations. The volume’s sceneries and stories take inspiration from the fantasy counterparts of India, Central and South America, Southeast Asia, and other areas.

The artwork in The Legend of Bold Riley may change from story to story, but Riley is always Bold Riley. She’s a fantastic and exceptionally appealing character, a dashing and daring young woman with strengths and weaknesses, remarkable talents, and human flaws. Although Riley’s sexuality is never the focus of the comic, it’s always a part of who she is as a person and as a well-rounded character. She falls in love, she makes mistakes, and she struggles and is challenged when faced with a world that’s not always black and white or even kind. The Legend of Bold Riley, while something new and refreshing, somehow also feels very familiar. It’s a collection of heroic tales, some ending in triumph and others ending in heartbreak. Because of its episodic nature there’s not a lot of character development, but Riley is such a great character to begin with that the work is still very satisfying. I thoroughly enjoyed The Legend of Bold Riley and look forward to reading more of Riley’s adventures in the future.