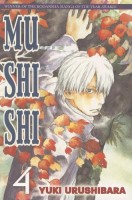

Creator: Yuki Urushibara

Creator: Yuki Urushibara

U.S. publisher: Del Rey

ISBN: 9780345499233

Released: May 2008

Original release: 2003

Awards: Japan Media Arts Award, Kodansha Manga Award

Although the ten-volumes series Mushishi was Yuki Urushibara’s professional debut as a mangaka, it has been very well-received by both critics and fans. The manga began its serialization in 1999 and would go on to win a Japan Media Arts Award in 2003 and a Kodansha Manga Award in 2006 among other honors and recognitions. Mushishi, Volume 4 was originally published in Japan in 2003. In 2008, Del Rey Manga released the first English-language edition which is now sadly out-of-print. However, as of 2014, the volume has been made available digitally by Kodansha Comics. Mushishi was a series that I stumbled upon when it was initially being released in English. The manga quickly became and continues to be one of my favorite series; Mushishi was one of the first manga that I made a point to collect in its entirety. I love the series’ quiet, creepy atmosphere, its emphasis on life and nature, and the influence of traditional Japanese culture and folklore on the stories being told.

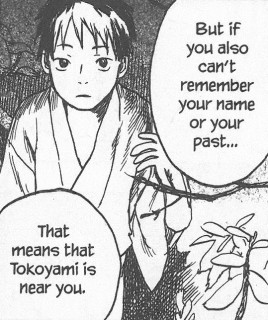

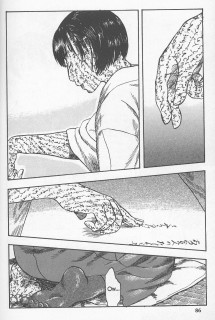

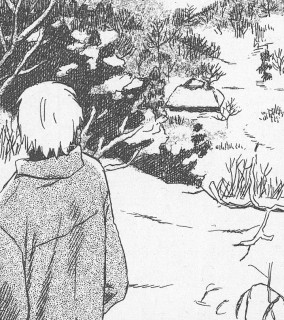

Mushishi, Volume 4 collects five stories. The volume opens with “Picking the Empty Cocoon,” telling the tale of a family with close connections to both mushi and mushishi. They are the caretakers of uro, a particularly useful but dangerous type of mushi. In “One-Night Bridge,” Ginko is invited to a remote village in a deep valley to investigate the case of a young woman who fell to the bottom of the gorge but somehow survived. Except that she’s never been the same since her accident. Plants growing out of season allow a brother and sister to weather harsh winters in “Spring and Falsehoods,” but the mushi that cause the phenomenon aren’t as benign as they first appear. In the fourth story, while traveling through the mountains, Ginko stumbles upon a small family living in a vast bamboo grove. They seem to be trapped there, unable to leave no matter how hard they try; they always end up circling back to their home. The volume concludes with “The Sound of Trodden Grass,” which provides a little more insight into Ginko’s past.

For the most part, Mushishi tends to be fairly episodic. Except for the presence of Ginko, out of all of the stories included in the fourth volume only “The Sound of Trodden Grass” has an explicit connection to any of the other chapters in the series, and it’s only a tangential one. Although none of the stories in Mushishi, Volume 4 are directly related to one another plot-wise, there was one similarity shared between them all that particularly struck me: the prominent role played by families. Looking back, this actually isn’t at all an uncommon theme in Mushishi—families, as well as other tightly knit communities and groups, are frequently featured in the manga. However, through the illness and other problems that follow them, mushi are shown to cause great strife in those relationships. Circumstances caused by mushi’s existence can drive people apart, but in some cases they may actually draw them together. Familial ties are strong and not easily broken, but mushi’s close connection to nature and life and death (including those of humans) is sometimes in conflict with them and they are just as enduring.

For the most part, Mushishi tends to be fairly episodic. Except for the presence of Ginko, out of all of the stories included in the fourth volume only “The Sound of Trodden Grass” has an explicit connection to any of the other chapters in the series, and it’s only a tangential one. Although none of the stories in Mushishi, Volume 4 are directly related to one another plot-wise, there was one similarity shared between them all that particularly struck me: the prominent role played by families. Looking back, this actually isn’t at all an uncommon theme in Mushishi—families, as well as other tightly knit communities and groups, are frequently featured in the manga. However, through the illness and other problems that follow them, mushi are shown to cause great strife in those relationships. Circumstances caused by mushi’s existence can drive people apart, but in some cases they may actually draw them together. Familial ties are strong and not easily broken, but mushi’s close connection to nature and life and death (including those of humans) is sometimes in conflict with them and they are just as enduring.

The stories in Mushishi are often reminiscent of folktales and legends originating from Japan; Urushibara clearly draws some inspiration directly from that lore. For example, “In the Cage” with its children born of bamboo recalls the story of Kaguya-hime. The fourth volume of Mushishi is influenced by Japanese history, as well. “The Sound of Trodden Grass” features a group of wanderers displaced by mushi known as the Watari who are based on the Sanka people of Japan. (This is even more meaningful to me now after having read Kazuki Sakuraba’s novel Red Girls: The Legend of the Akakuchibas in which the Sanka also play a part.) Some of Mushishi‘s stories can be rather spectacular, with mushi causing phenomena verging on the paranormal, while others are more subdued. Mushi are said to be very close to the original form of life and are therefore inseparable from nature, but they remain mysterious. Mushishi is a collection of tales that delve into that terrifying unknown. Urushibara combines elements of folklore and history along with her own imagination to successfully create a series that feels familiar while still being new.