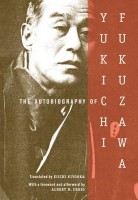

Author: Yukichi Fukuzawa

Author: Yukichi Fukuzawa

Translator: Eiichi Kiyooka

U.S. publisher: Columbia University Press

ISBN: 9780231139878

Released: January 2007

Original release: 1897

Yukichi Fukuzawa—scholar, translator, author, and educator, among many other things—is one of Japan’s most influential historical figures of the modern era, helping to shape the country as it is known today. As the founder of Keio University whose writings continue to be taught and whose likeness appears on the 10,000 yen banknote, there are very few Japanese to whom Fukuzawa is entirely unknown. Fukuzawa’s life was recently brought to my attention while reading Minae Mizumura’s The Fall of Language in the Age of English which discussed some of his influence and included excerpts of his autobiography. Intrigued by this, I decided to read the work in its entirety. The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa was originally dictated by Fukuzawa in 1897. The first English translation by Eiichi Kiyooka, Fukuzawa’s grandson, appeared in 1934 and was later revised in 1960. Many editions of The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa have been released in English, but the most recent was published in 2007 by Columbia University Press.

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa originated from a request by a foreigner interested in Fukuzawa’s account of the time period leading up to and surrounding the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Fukuzawa narrated the story of his life fairly informally in 1897 and soon after edited, annotated, and published the transcribed manuscript. He intended to write a more formal and comprehensive companion volume, but he died in 1901 before it was completed. The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa begins with Fukuzawa’s childhood and follows his life into his old age. Fukuzawa was born in 1835 in Osaka into a samurai family originally from Nakatsu, where he grew up. From an early age, Fukuzawa showed interest in Western learning, first studying Dutch (at the time the only foreign influence permitted within Japan) and the eventually English. He was very passionate about language as a tool to access new knowledge and understanding, and he served on multiple missions to America and Europe as an interpreter and translator. But his interest in the West also put him in danger during a time when anti-foreign sentiment was rampant in Japan.

The various editions of The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa available in English are primarily distinguished by the accompanying materials included to supplement Fukuzawa’s main text. The most recent release from Columbia University Press offers several useful additions, some of which were available in previous editions or which were published elsewhere. Albert Craig, an academic and historian whose work focuses on Japan, provides the volume’s foreword as well as its lengthy afterword “Fukuzawa Yukichi: The Philosophical Foundations of Meiji Nationalism.” Originally published in 1968 in the the volume Political Development in Modern Japan, the afterword places Fukuzawa and his ideals into greater historical and political context. Also included in Columbia’s recent edition of The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa are two appendices—a chronological table outlining the events in Fukuzawa’s life and in world history and a translation of Fukuzawa’s influential essay “Encouragement of Learning”—as well as copious notes and an index.

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa is a surprisingly engaging, entertaining, and even humorous work. In his autobiography, Fukuzawa comes across as very amicable, down-to-earth, and forward-thinking. I particularly enjoyed Fukuzawa’s invigorating account of his experiences as a young man who was devoted to his studies, but who would also willingly participate in the revelry, antics, and pranks of his fellow students. Speaking of how drunken “nudeness brings many adventures” and such other things greatly humanizes a person primarily known for his impressive accomplishments. As Fukuzawa matured, he played a pivotal role in the development of the Japanese education system. While he introduced many Western concept and ideas in his pursuit of knowledge, at heart Fukuzawa was a nationalist who abhorred the violent methods of many of his contemporaries. The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa provides not only a fascinating look into the life of Fukuzawa, it provides a glimpse into a particularly tumultuous and transformative period of time in Japan’s history.