Creator: Setona Mizushiro

Creator: Setona Mizushiro

U.S. publisher: Go! Comi

ISBN: 9781933617701

Released: November 2008

Original release: 2007

After School Nightmare is a ten-volume manga series by Setona Mizushiro. Darkly psychological with elements of horror as well as social commentary, After School Nightmare can at times be a deeply troubling and challenging read while still being engrossing and oddly compelling. I first started reading the series several years ago, but have only recently been able to bring myself to read beyond the first few volumes of the manga, largely because I did find it so disconcerting and hard-hitting. Granted, the dark, anxiety-ridden atmosphere which makes the After School Nightmare so intimidating to approach is also what makes the story particularly effective and is an aspect to the manga that I can appreciate. After School Nightmare, Volume 9 was first published in Japan in 2007. The English-language edition of the volume was released in 2008 by Go! Comi. Sadly, the entire series has now gone out of print and is becoming more difficult to find.

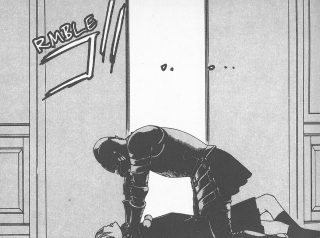

One by one the students participating in the special after school class which forces them to share their literal nightmares with one another are graduating and disappearing, leaving only a vague memory of their existence behind. Though at times vicious and cruel, the dreams are intended to allow the students to work through their personal traumas, crises, and fears so that they can let go and move on from their troubled pasts. However, the violence and turmoil they experience within the dreams frequently spills over into their waking lives and graduating doesn’t necessarily guarantee a peaceful resolution. Koichiro in particular has reached his breaking point. He is ruthless in his determination to graduate and leave his overbearing and abusive father behind along with his carefully crafted public persona. Triggered by outside events, the nightmare Koichiro brings down upon the other students as he tries to free himself turns into a shockingly brutal and bloody rampage, signalling the beginning of the end for himself and for those who still remain.

A few questions still remain, but for the most part Koichiro’s character arc is resolved in After School Nightmare, Volume 9. Like so many of the other characters’ stories, Koichiro’s is a tragic one and it is heartwrenching to see it play out. The culmination of his anger, pain, and suffering has a direct and devastating impact on the others, ending with a violent attack on Mashiro, the portrayal of which has blatant parallels to a sexual assault. Koichiro was at one point the most stable and seemingly well-adjusted character in the series, so to see such a drastic shift in his outward attitude and behavior is especially startling. He isn’t the only character to have significantly changed over the course of After School Nightmare, though. However, for some the process, while still being extraordinarily difficult, has ultimately been more positive. Just as the dreams have led Koichiro to abandon his self-restraint, they have also allowed Mashiro the freedom to begin to come to terms with his fluid gender identity and the fact that he may feel more comfortable as a girl. Compared to the beginning of the series, Mashiro has greatly matured.

A few questions still remain, but for the most part Koichiro’s character arc is resolved in After School Nightmare, Volume 9. Like so many of the other characters’ stories, Koichiro’s is a tragic one and it is heartwrenching to see it play out. The culmination of his anger, pain, and suffering has a direct and devastating impact on the others, ending with a violent attack on Mashiro, the portrayal of which has blatant parallels to a sexual assault. Koichiro was at one point the most stable and seemingly well-adjusted character in the series, so to see such a drastic shift in his outward attitude and behavior is especially startling. He isn’t the only character to have significantly changed over the course of After School Nightmare, though. However, for some the process, while still being extraordinarily difficult, has ultimately been more positive. Just as the dreams have led Koichiro to abandon his self-restraint, they have also allowed Mashiro the freedom to begin to come to terms with his fluid gender identity and the fact that he may feel more comfortable as a girl. Compared to the beginning of the series, Mashiro has greatly matured.

After School Nightmare, Volume 9 has a fair number of major plot twists, surprising reveals, and crucial story developments, many of which call into question everything that has come before in the manga. Some of these things have been foreshadowed and are not entirely surprising but there is still some disorientation as they are revealed to be not quite what they initially seemed. Koichiro dominates the first few chapters of the ninth volume but from there the focus of the manga turns toward Sou as more of his backstory is explored. An explanation of a past that he has not entirely dealt with yet and that has been incredibly damaging both emotionally and psychologically is finally given. After School Nightmare was never a light series, but the ninth volume is a particularly heavy and dramatic one. Considering the very final scene which challenges many of the assumptions that I had made regarding the series, I am very curious to see where Mizushiro takes the story in the final volume. After School Nightmare has been a dark and twisting journey and I have no idea how it will end; I’m almost a little frightened to find out.