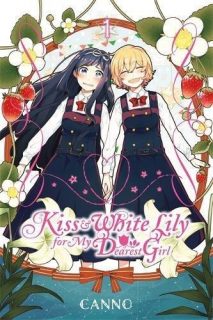

It’s been some time since Experiments in Manga has hosted a guest post, but my friend Jocilyn was once again inspired and is back to review one of the more recently released yuri manga, the first volume of Canno’s Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl. (Also if you’re interested, you can find some of Jocilyn’s non-manga writings over at her delectable tea blog Parting Gifts!)

* * *

Seeing Canno’s name on the cover of a book in English feels like quite the sea change. Not only is she somewhat obscure with only one full manga series and a couple of one-offs and anthology contributions to her name, her writing style also leans heavily toward the heart-throbbingly romantic yuri (which English publishers have traditionally avoided as being too risky/niche). Also, although not an uncommon setting for yuri manga, Canno’s Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is the first genre title in English in a decade (i.e. Hakamada Mera’s Last Uniform and Hayashiya Shizuru’s Hayate X Blade, neither of which are exactly realistic), to give us a long look at dorm-life in a prestigious all-girls’ school. Finally, in case those weren’t enticing enough reasons, “Ano Kiss” has been translated by the matchless Jocelyne Allen, easily the most talented and enjoyable manga translator in the industry (and kind of my personal heroine). Hands down, Kiss & White Lily was my most anticipated manga of the year, and it has not disappointed.

Seeing Canno’s name on the cover of a book in English feels like quite the sea change. Not only is she somewhat obscure with only one full manga series and a couple of one-offs and anthology contributions to her name, her writing style also leans heavily toward the heart-throbbingly romantic yuri (which English publishers have traditionally avoided as being too risky/niche). Also, although not an uncommon setting for yuri manga, Canno’s Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is the first genre title in English in a decade (i.e. Hakamada Mera’s Last Uniform and Hayashiya Shizuru’s Hayate X Blade, neither of which are exactly realistic), to give us a long look at dorm-life in a prestigious all-girls’ school. Finally, in case those weren’t enticing enough reasons, “Ano Kiss” has been translated by the matchless Jocelyne Allen, easily the most talented and enjoyable manga translator in the industry (and kind of my personal heroine). Hands down, Kiss & White Lily was my most anticipated manga of the year, and it has not disappointed.

To briefly summarize the plot, Ayaka Shiramine was told as a child that a 95/100 was an unacceptably low grade and ever since has never settled for anything less than no.1 in her class. Enter Yurine Kurosawa, a genius transfer student who can work academic and PE miracles with seemingly zero effort, who’s constantly seen sleeping in class. Indignant of the presumptuous upstart, Shiramine tries even harder than usual but still only manages second place on their midterms. In a fit of pique, Shiramine rips up her 98/100 test in front of Kurosawa declaring “It’s no good unless it’s perfect. If only you weren’t here, I would still be no.1” Kurosawa who had initially been impressed and quite smitten with Shiramine, amps up the rivalry and lords her superiority over Shiramine as a means to get closer to her. Before long Kurosawa has stolen Shiramine’s first kiss and being somewhat tsundere, Shiramine goes into total denial mode before being caught in a compromising position by her roommate cousin. Naturally, being a yuri manga, the cousin represents a B-story involving the boyish star of the track team and a hotly akogared sempai. Yada Yada Yada.

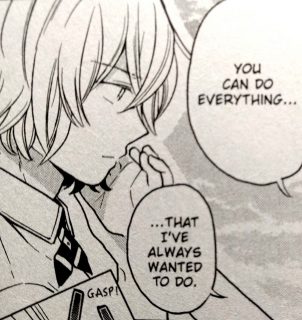

I won’t belabor the obvious parallel to Kare Kano in overall plot. Kurosawa’s utter genius and complete ambivalence to nearly everything that doesn’t involve Shiramine is oddly cute and compelling. One scene that paints Kurosawa as particularly superhuman had me in stitches for a while the first time I read it, but I won’t spoil it for you here. Although Shiramine might be outwardly cool and dissembling toward Kurosawa, when they’re alone together she manages to unwittingly send all the right signals. As with its inspiration, the honor students’ relationship is all blushes and awkward but swoon-worthy and adorable.

I won’t belabor the obvious parallel to Kare Kano in overall plot. Kurosawa’s utter genius and complete ambivalence to nearly everything that doesn’t involve Shiramine is oddly cute and compelling. One scene that paints Kurosawa as particularly superhuman had me in stitches for a while the first time I read it, but I won’t spoil it for you here. Although Shiramine might be outwardly cool and dissembling toward Kurosawa, when they’re alone together she manages to unwittingly send all the right signals. As with its inspiration, the honor students’ relationship is all blushes and awkward but swoon-worthy and adorable.

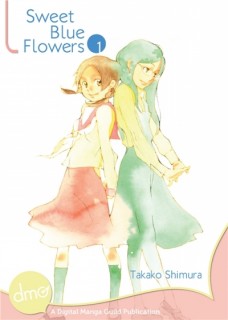

Kiss & White Lily variously waxes exciting shoujo romance and lighthearted school girl fun in an enticing mixture. Although Canno does tend to use a lot of screen tones to the point of necromancing Kare Kano, her art style is very cute and emotive, moreso reminiscent of Shimura Takako. I very much enjoyed the gorgeous full-color introductory pages Yen was good enough to reproduce. Naturally Kiss & White Lily’s translation is nigh seamless perfection. I honestly cannot produce a single gripe this time. A thoroughly fabulous read!