Creator: Nanao

Creator: Nanao

Original story: HaccaWorks*

U.S. publisher: Yen Press

ISBN: 9780316351966

Released: December 2015

Original release: 2012

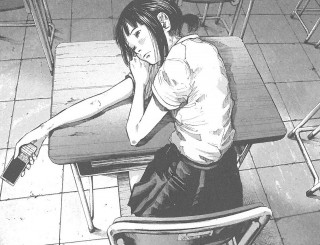

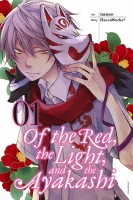

Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi was originally a visual novel developed and created by the doujin group HaccaWorks* that was released in 2011. The manga adaptation by another doujin creator, Nanao, began serialization in Japan in 2012. The first volume of the manga was also collected and released later that year. In English, the Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi manga is being released by Yen Press and debuted in late 2015. I haven’t actually played the original Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi, though I’m fairly certain it would be something that I would enjoy. In fact, I didn’t even known that the manga was based on a game when I first picked it up. Nor was I previously familiar with any of the creators involved which probably isn’t too surprising—I believe that Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi may very well be Nanao’s first professional work as a mangaka. But, due to the evocative and vaguely ominous cover art and title as well as the promise of the involvement of yokai, the series still caught my attention.

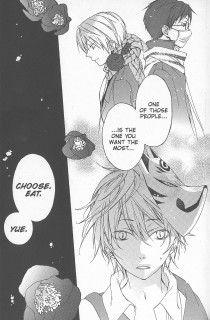

For as long as he can remember, Yue has lived at the mountain shrine associated with the town of Utsuwa where he has been taken care of by the local fox spirits and their attendants. Despite being told not to leave the mountain, Yue and Kurogitsune, one of his fox companions, sneak out of the shrine to attend the town’s festival. The new experience, although exciting, is somewhat overwhelming for Yue. But while at the festival, he encounters two young men who stand out to him more than anyone else—whereas most people appear as shadowy, indistinguishable figures to Yue, Tsubaki and Akiyoshi are distinctive and unique presences. Upon his return to the shrine Yue is duly scolded for breaking the rules but when the master learns about Akiyoshi and Tsubaki she encourages him to meet them again. The fate of all three boys are now intertwined. Because Yue finds himself so irresistibly drawn to Tsubaki and Akiyoshi, he is told that he will one day have to choose one of them to become his “meal,” necessary for sustaining his very existence.

I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed the first volume of Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi. The manga combines elements of folklore, horror, and mystery in a very satisfying way. Granted, after the first volume, readers are left with more questions than answers. Much about the series’ story, setting, and characters remain unclear at this point, but what is possibly implied is tantalizing. At times Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi can be unnecessarily cryptic—entire conversations are held in which the characters obviously know what they are talking about but readers aren’t given enough information or context to really understand or follow—which is more frustrating than mysterious, but this still sparks curiosity. I am genuinely intrigued by the series; I want to know more about the ominous events and strange disappearances occurring in Utsuwa, a place inhabited by both humans and spirits which seems to be some sort of threshold between worlds.

I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed the first volume of Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi. The manga combines elements of folklore, horror, and mystery in a very satisfying way. Granted, after the first volume, readers are left with more questions than answers. Much about the series’ story, setting, and characters remain unclear at this point, but what is possibly implied is tantalizing. At times Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi can be unnecessarily cryptic—entire conversations are held in which the characters obviously know what they are talking about but readers aren’t given enough information or context to really understand or follow—which is more frustrating than mysterious, but this still sparks curiosity. I am genuinely intrigued by the series; I want to know more about the ominous events and strange disappearances occurring in Utsuwa, a place inhabited by both humans and spirits which seems to be some sort of threshold between worlds.

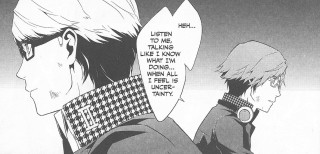

Utsuwa isn’t the only thing peculiar that’s peculiar in Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi. The characters, too, are all a bit odd. Yue goes through life in an almost dreamlike, innocent state, his real identity not only obscured to readers but to himself as well. Akiyoshi, with his eccentric behavior and flair for the dramatic, comes across as conspiracy theorist except that he actually has evidence and legitimate reasons to be concerned. Tsubaki would initially appear to be a fairly normal if somewhat moody young man if it wasn’t for the fact that humans and spirits alike frequently find themselves obsessed or enamored with him. The three form an curious bond as they begin to investigate the unusual happenings in Utsuwa. They’re not exactly friends but are far more than mere acquaintances. Supported by Nanao’s attractive (if occasionally cluttered) artwork, intriguing characters, and an effective sense of mystery and impending misfortune, Of the Red, the Light, and the Ayakashi has a dark, otherworldly atmosphere which I’m really enjoying.