Creator: Jim Zub and Steve Cummings

Creator: Jim Zub and Steve Cummings

Publisher: Image Comics

ISBN: 9781632154033

Released: August 2015

Original run: 2015

Ties That Bind is the second volume of the American comic series Wayward, created by Jim Zub and Steve Cummings and released by Image Comics. Anything having to do with yokai immediately catches my attention, and I had previously read and enjoyed some of Zub’s earlier work, so I was very interested in reading Wayward. I thoroughly enjoyed the first collected volume in the series, String Theory, meaning that there was absolutely no question that I would be picking up the second, too. (Well, at least that was the case before I learned that a deluxe omnibus edition was going to be released—then there was a difficult choice to be made.) Ties That Bind, published in 2015, collects the sixth through tenth issues of Wayward which were originally serialized between March and July 2015. Also included is an introduction by Charles Soule as well as several yokai essays by Zack Davisson which I especially appreciate. For this particular volume, Zub is credited for the story and Cummings for the line art while the credit for the color art goes to Tamara Bonvillain and color flats to Ludwig Olimba.

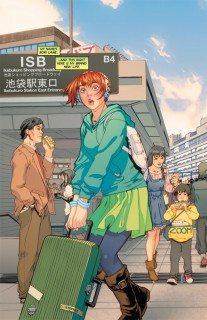

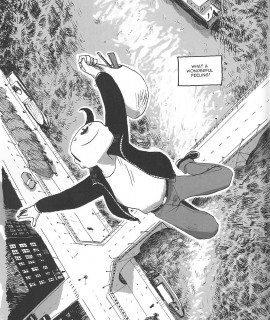

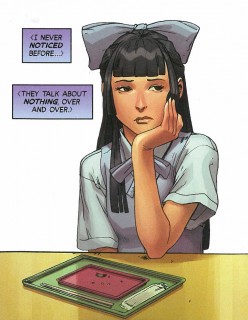

Emi Ohara’s life follows a simple, predictable routine. Without much variation from day to day she wakes up, goes to school, and returns home. But Emi yearns to have the exciting lives that the heroines of her favorite shoujo manga enjoy. Little does she know that she’ll get what she wished for, but not at all in the way that she expected—Emi discovers she has the ability to manipulate her body and the materials around her in astonishing ways. Suddenly, among other strange developments, her touch is able to melt and mold plastic and her arm can take on the characteristics of metal and glass. At first she thinks it’s all a dream, but then she is chased down by a group of monstrous kitsune only to be rescued by Ayane and Nikaido, two young people who have their own special powers and who are also the yokai’s targets. It’s been three months since the other members of their group, Rori and Shirai, disappeared during the chaos of an epic confrontation with a faction of yokai. At this point Ayane and Nikaido are welcoming any allies they can find, and that includes Emi.

Whereas String Theory largely followed Rori’s perspective of the supernatural events unfolding in Tokyo, much of the focus of Ties that Bind is on Emi. Some of the contrasts between the young women as two of the leads in the story are particularly interesting. Rori, who is half-Japanese and half-Irish, is often considered to be an outsider within Japanese society. Emi, on the other hand, is a “proper Japanese girl,” dutiful and obedient even though she finds that role to be increasingly suffocating. Rori is a Weaver with the ability to alter reality and change a person’s fate. (Just how incredibly powerful and far-reaching her talents truly are is still in the process of being revealed, but the continuing development and evolution of her skills in Ties That Bind is impressive.) However, Emi, who like Rori is sensitive to patterns and seems to be able to at least partially identify the course of fate and destiny, feels trapped and unable to make meaningful choices or to change the direction of those events that have already been set in motion.

Whereas String Theory largely followed Rori’s perspective of the supernatural events unfolding in Tokyo, much of the focus of Ties that Bind is on Emi. Some of the contrasts between the young women as two of the leads in the story are particularly interesting. Rori, who is half-Japanese and half-Irish, is often considered to be an outsider within Japanese society. Emi, on the other hand, is a “proper Japanese girl,” dutiful and obedient even though she finds that role to be increasingly suffocating. Rori is a Weaver with the ability to alter reality and change a person’s fate. (Just how incredibly powerful and far-reaching her talents truly are is still in the process of being revealed, but the continuing development and evolution of her skills in Ties That Bind is impressive.) However, Emi, who like Rori is sensitive to patterns and seems to be able to at least partially identify the course of fate and destiny, feels trapped and unable to make meaningful choices or to change the direction of those events that have already been set in motion.

At times, Wayward can be an extremely violent series. Ayane’s way of taking charge of the situation is to go on the attack, dragging Nikaido and Emi along with her. The yokai, threatened by the very existence of the supernaturally-gifted teens, are more than willing to fight back. The resulting battles are intense, bloody, and even gruesome. But the yokai aren’t united in their efforts—Ties That Bind introduces the tsuchigumo, or dirt spiders, who would seem to have their own agenda. I love that Wayward incorporates the lore and, especially in the case of the dirt spiders, the history surrounding yokai. The series’ interpretation of yokai and traditional tales is its own and is closely integrated with an entirely new, contemporary story. Wayward effectively creates a cohesive and compelling narrative that can be enjoyed by readers who are already familiar with yokai as well as by those who are not. Ties That Bind brings together new characters, new conflicts, and new plot threads while expanding and further developing those that had already been established. Wayward is an excellent series with great art, characters, and story; I’m definitely looking forward to the next volume.