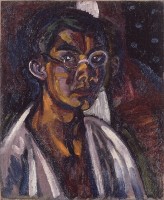

Kaita Murayama, born in 1896, was a Japanese artist, poet, and author. He was best known for his work as an artist, and especially for the originality and vibrancy of his paintings. Although some of his writings were printed while he was alive, most of Murayama’s poetry and prose was collected and published by his friends after his death in 1919 of tuberculosis. Very little has actually be written about Murayama in English. Likewise, very little of his work has been translated. This is unfortunate because both Murayama and his writings are fascinating.

Kaita Murayama, born in 1896, was a Japanese artist, poet, and author. He was best known for his work as an artist, and especially for the originality and vibrancy of his paintings. Although some of his writings were printed while he was alive, most of Murayama’s poetry and prose was collected and published by his friends after his death in 1919 of tuberculosis. Very little has actually be written about Murayama in English. Likewise, very little of his work has been translated. This is unfortunate because both Murayama and his writings are fascinating.

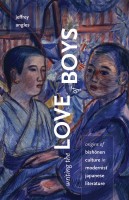

I had previously encountered a few of Murayama’s paintings, but it wasn’t until I read Jeffrey Angles’ academic work Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishōnen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature (released by the University of Minnesota Press in 2011) that I discovered Murayama as an author. This isn’t terribly surprising as only two of Murayama’s short stories have so far been released in English in their entirety—”The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” and “The Diabolical Tongue”—both of which are discussed at length in Writing the Love of Boys and both of which were translated by Angles. Writing the Love of Boys is a particularly interesting examination of the portrayal of male-male desire in Japanese literature during the early twentieth century with a specific focus on Kaita Murayama, Edogawa Rampo, and Taruho Inagaki. After reading Angles’ translated excerpts and analyses of Murayama’s work, and because I wasn’t previously aware of Murayama’s writing, my curiosity was piqued; I wanted to experience his stories for myself.

I had previously encountered a few of Murayama’s paintings, but it wasn’t until I read Jeffrey Angles’ academic work Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishōnen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature (released by the University of Minnesota Press in 2011) that I discovered Murayama as an author. This isn’t terribly surprising as only two of Murayama’s short stories have so far been released in English in their entirety—”The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” and “The Diabolical Tongue”—both of which are discussed at length in Writing the Love of Boys and both of which were translated by Angles. Writing the Love of Boys is a particularly interesting examination of the portrayal of male-male desire in Japanese literature during the early twentieth century with a specific focus on Kaita Murayama, Edogawa Rampo, and Taruho Inagaki. After reading Angles’ translated excerpts and analyses of Murayama’s work, and because I wasn’t previously aware of Murayama’s writing, my curiosity was piqued; I wanted to experience his stories for myself.

The first short story by Murayama to be translated and published in English was “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino,” which was included in Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913–1938. The volume, edited by William J. Tyler and released by the University of Hawai’i Press in 2008, is the first major anthology of Japanese modernist short stories to be translated and analyzed in English. “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” isn’t a well-known story in Japan. However, it is the first work included in Modanizumu and is noted as being representative of early, experimental modernist prose. It incorporates themes of same-sex desire and the spectacular, both of which were not at all uncommon in modernist Japanese literature. Murayama wrote “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino” between 1913 and 1914, soon before making the decision to leave Kyoto to study art in Tokyo, but it wasn’t actually published until 1921. The story is short, barely over two pages long, but it leaves a strong impression. In it a young man is wandering through a city at night when he has a vision of the head of Salaino, a beautiful youth whom he loves, after which he is confronted by an apparition of Leonardo da Vinci. Murayama’s writing is highly visual and descriptive, almost hallucinatory, and intensely erotic. This atmospheric quality can be seen beginning with the very first line—”It was a night thick with yearning, a yearning so viscous that it was as if dark purple and precious black liqueurs had replaced the air and covered the earth.”—and continues through to the very end. “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” is a lush, surreal, and dreamlike tale, but it can also be read as an allegory challenging the dominance of Western art.

The first short story by Murayama to be translated and published in English was “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino,” which was included in Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913–1938. The volume, edited by William J. Tyler and released by the University of Hawai’i Press in 2008, is the first major anthology of Japanese modernist short stories to be translated and analyzed in English. “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” isn’t a well-known story in Japan. However, it is the first work included in Modanizumu and is noted as being representative of early, experimental modernist prose. It incorporates themes of same-sex desire and the spectacular, both of which were not at all uncommon in modernist Japanese literature. Murayama wrote “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino” between 1913 and 1914, soon before making the decision to leave Kyoto to study art in Tokyo, but it wasn’t actually published until 1921. The story is short, barely over two pages long, but it leaves a strong impression. In it a young man is wandering through a city at night when he has a vision of the head of Salaino, a beautiful youth whom he loves, after which he is confronted by an apparition of Leonardo da Vinci. Murayama’s writing is highly visual and descriptive, almost hallucinatory, and intensely erotic. This atmospheric quality can be seen beginning with the very first line—”It was a night thick with yearning, a yearning so viscous that it was as if dark purple and precious black liqueurs had replaced the air and covered the earth.”—and continues through to the very end. “The Bust of the Beautiful Young Salaino” is a lush, surreal, and dreamlike tale, but it can also be read as an allegory challenging the dominance of Western art.

The second of Murayama’s stories to be translated into English was “The Diabolical Tongue.” It was included in Tales of the Metropolis, the third and final volume of Kurodahan Press’ series Kaiki: Uncanny Tales from Japan, released in 2012. Kaiki, which collects weird and supernatural Japanese short stories, is edited by Higashi Masao, who specializes in kaidan—tales of the strange and mysterious. “The Diabolical Tongue” was published in 1915 and was one of Murayama’s last works to overtly deal with male-male desire, though it is perhaps not as obviously homoerotic as “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino.” It reminded me quite a bit of some of Edogawa Rampo’s stories, which makes sense as Murayama was one of Rampo’s direct inspirations. “The Diabolical Tongue” was a precursor of ero guro nonsense, a literary movement which came into prominence in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s. The story incorporates themes which are frequently found in ero guro—decadence, eroticism, mystery—as well as archetypal elements of the bizarre, grotesque, and taboo. Like “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino,” an important part of “The Diabolical Tongue” focuses on a young man who wanders a city at night in search of his desires. He satisfies his unusual appetite and cravings by eating stranger and stranger things until he is finally driven to cannibalism. He is particularly drawn towards beautiful young men and women, imaging how exquisite they will taste. Unlike “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino,” which ends in ecstasy, “The Diabolical Tongue” is fundamentally a tragic and horrifying tale that begins and ends in death. It is deliciously disconcerting, very much in the same vein as the ero guro literature which would soon follow.

The second of Murayama’s stories to be translated into English was “The Diabolical Tongue.” It was included in Tales of the Metropolis, the third and final volume of Kurodahan Press’ series Kaiki: Uncanny Tales from Japan, released in 2012. Kaiki, which collects weird and supernatural Japanese short stories, is edited by Higashi Masao, who specializes in kaidan—tales of the strange and mysterious. “The Diabolical Tongue” was published in 1915 and was one of Murayama’s last works to overtly deal with male-male desire, though it is perhaps not as obviously homoerotic as “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino.” It reminded me quite a bit of some of Edogawa Rampo’s stories, which makes sense as Murayama was one of Rampo’s direct inspirations. “The Diabolical Tongue” was a precursor of ero guro nonsense, a literary movement which came into prominence in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s. The story incorporates themes which are frequently found in ero guro—decadence, eroticism, mystery—as well as archetypal elements of the bizarre, grotesque, and taboo. Like “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino,” an important part of “The Diabolical Tongue” focuses on a young man who wanders a city at night in search of his desires. He satisfies his unusual appetite and cravings by eating stranger and stranger things until he is finally driven to cannibalism. He is particularly drawn towards beautiful young men and women, imaging how exquisite they will taste. Unlike “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino,” which ends in ecstasy, “The Diabolical Tongue” is fundamentally a tragic and horrifying tale that begins and ends in death. It is deliciously disconcerting, very much in the same vein as the ero guro literature which would soon follow.

Personally, I would love to see more of Murayama’s work translated into English and to read more of his poetry (examples of which can be found in Writing the Love of Boys) as well as his prose. I am aware and do understand how unlikely that is to happen. Poetry is notoriously difficult to translate and the demand for century-old short stories, as much as I and others would be interested in reading them, is generally low. However, I am glad that “The Bust of the Beautiful Salaino” and “The Diabolical Tongue” have been translated. The two stories share some commonalities but are ultimately very different from each other, exhibiting the versatility and range of Murayama’s creative output.