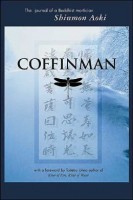

Author: Shinmon Aoki

Author: Shinmon Aoki

Translator: Wayne Yokoyama

U.S. publisher: Buddhist Education Center

Released: January 2002

Original release: 1993

Shinmon Aoki’s Coffinman: The Journal of a Buddhist Mortician was originally brought to my attention when I learned that Yōjirō Takita’s 2008 film Departures (which I love) was loosely based on the work. I came across the title again when I was looking into embalming practices in Japan. Embalmers are a rarity in a country where cremation soon after death is almost exclusively practiced. Instead, bodies are generally prepared for funeral by a nokanfu, or “coffinman.” Aoki’s autobiographical Coffinman was initially published in Japan in 1993. The Buddhist Education Center released the book in English in 2002 with a translation by Wayne Yokoyama. Also included in the volume is a foreword by Taitetsu Unno, the author of River of Fire, River of Water, a major work and introduction to Pure Land Buddhism in English.

Nearly thirty years before writing Coffinman, Shinmon Aoki pursued the unusual career more out of necessity than by choice when he and his family were facing bankruptcy. The profession, as well as others that deal with the dead, is looked down upon and even reviled by some, the taboo and impurity associated with death extending to those who make their living from it. After becoming a coffinman, Aoki lost friends and was shunned by family members. When his wife discovered what his new job entailed even she was incredibly upset by it. But Aoki provided an important and needed service to those left behind to grieve the loss of their loved ones as well as for the dead who had no one to mourn for them. Working so closely with corpses day after day put Aoki in a position to understand what death and life really means in both physical and spiritual contexts. It’s not happy work, but death is also not something to fear.

Coffinman is divided into three chapters but can also be seen as consisting of two parts. The first two chapters, “The Season of Sleet” and “What Dying Means” make up the first part of Coffinman. In them Aoki relates personal anecdotes and stories about his career as a coffinman—how he came to be employed, people’s reactions to him and the job, how working in an environment surrounded by death changed him and his way of thinking, and so on. He frequently uses poets and poetry as a way to express his thoughts to the reader. The third and longest chapter, “The Light and Life,” makes up the second half of the book. Although Aoki’s personal recollections can still be found in this section, the focus turns to the role of death in Shin Buddhism (the largest sect of Japanese Buddhism) from a layperson’s perspective.

Particularly when reading the second half of Coffinman it does help to have some basic understanding of Buddhism. However, it is not absolutely necessary as plenty of end notes are provided for guidance. Additionally, Aoki’s style of writing is very personable and approachable even for those who might not have a familiarity with Buddhism. Many of Aoki’s philosophical musings, such as those dealing with the relationship between religion and science or how society as a whole has come to view life and death, are not only applicable to Buddhist ways of thought. Although there is a strong sense of spirituality throughout the book, it is only the second half that focuses on the more religious aspects of the subject matter. As interesting as I found Aoki’s reflections on Buddhism, what appealed to me most about Coffinman were the more autobiographical elements of the work—the impact that becoming a coffinman had on his life and how that career fits into the culture of Japan.