As of 2016, I have now attended the Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF) for four years running. TCAF is still the only large comics event that I make a point to attended, although I guess technically I went to an anime/manga/cosplay convention earlier this year since I and the rest of the taiko group I’m a part of were featured guest performers. Anyway, I digress. TCAF is an amazing event and I’m able to enjoy a fair amount of it even though my anxiety (social and otherwise) sometimes prevents me from doing everything that I’d really like to. Each year I attend seems to be a little easier for me, though it’s still certainly not easy. But, I do think TCAF is totally worth trying to push through my issues when I can, which probably says a fair amount about the event itself.

Like last year, TCAF 2016 turned into a family trip, which made me happy. The four of us arrived in Toronto late Thursday afternoon, settled into where we were staying, stretched our legs in a nearby park (which was much needed after spending hours cooped up in the car), and eventually found something to eat for dinner before turning in for the night. Originally, I was hoping and planning to go to the opening of Shintaro Kago’s solo exhibition at Narwhal, but for a variety of reasons I ended up deciding to chill with the family all night instead. Which was also good, since for all intents and purposes TCAF ends up being a vacation of sorts for us all.

Friday, too, was more of a family day, although I did meet up with Jocelyne Allen (who translates Japanese novels and manga, and who is one of the interpreters for TCAF) for coffee in the morning. We chatted about taiko, translation, TCAF, Toronto, Tokyo and all sorts of other things, which was highly enjoyable. It was nice being able to find some time to talk with her in person since we primarily only know each other online and she’s understandably very busy during TCAF. Most of the rest of the day was spent exploring Toronto with the family, including the Royal Ontario Museum which had a really interesting exhibit—A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints—about gender and sexuality in Edo-era Japan. Finally, that evening I made my way to the tail end of Sparkler Monthly‘s annual TCAF mixer. It was a fairly small group when I got there, but a good time was had by all, myself included.

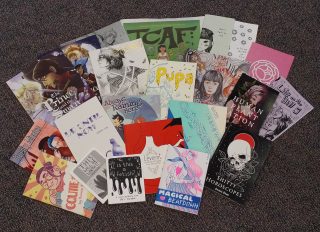

Saturday marks the beginning of TCAF proper, although there are plenty of related events that occur both before and after TCAF weekend. As was the case for the previous couple of years, I started off the 2016 festival in the in the exhibitors’ area before most of the main programming began. I ended up spending my entire comics budget for the weekend before the first day was over, but I was pretty happy with my haul which included some pre-orders, a couple of Kickstarter pickups, a few things I knew beforehand that I wanted to buy, as well as several unplanned, spur-of-the-moment purchases.

This year I actually spent even more time on the exhibit floors buying comics, collecting sketches and signatures, and talking to creators than I have in the past. (A few highlights: I was particularly excited to meet Saicoink, whose comic Open Spaces and Closed Places I love, made a point to tell Kori Michele Handwerker how much Portals meant to me, and discovered some wonderful new-to-me creator’s like GQutie‘s Ronnie Ritchie.) That, combined with prioritizing the family more and considering the need for flexible schedules when dealing with a not-quite-two-year old, meant that I didn’t make it to as many panels this year. In some ways, TCAF 2016 for me felt more like TCAF-lite, but I still greatly enjoyed the festival and was thoroughly satisfied by all of the events, panels, and interviews that I was able to attend.

On Saturday, I ended up making it to four panels. The first was the Spotlight on Shintaro Kago, one of TCAF’s featured guests for 2016, who was interviewed by Youth in Decline’s Ryan Sands. Kago is particularly well-known for his horrific, erotic, and grotesque manga and illustrations. Many of Kago’s works are released ero-manga magazines. As he pointed out, his manga isn’t the type of work that would be published in Jump; there is a limited number of magazines (generally erotic or alternative) that would even consider releasing his work. But by submitting to ero-magazines, Kago is allowed a tremendous amount of editorial freedom. As long as the minimum erotic requirements are met, he is able to do almost anything that he wants to with his manga, including highly experimental techniques. An example of this is a work known in English as “Abstraction” which gained a fair amount of international attention when it was translated by a fan and posted online. When asked about his feelings regarding fan translations, Kago responded that in his case he was satisfied with his work becoming more readily available to a worldwide audience since the benefits he received from the original release (page rates, etc.) didn’t amount to much anyway. Another of Kago’s short manga, “Punctures,” was officially translated in English in the anthology Secret Comics Japan. Anecdotally, it was one of the few works by Kago that the editors felt would be safe enough to include and sell. At the beginning of his creative career, Kago actually wanted to be involved in making films. However, he realized that movies are very difficult to make alone, and since he didn’t have any friends to make movies with, he turned to manga as a way to express himself so that he wouldn’t need to rely on others.

After spending a bit more time wandering the exhibitor areas, I then made my way to the panel “Depictions of Sex in Comics” which was moderated by Rebecca Sullivan, a scholar specializing in sex and media as well as gender and cultural studies. The panel featured a variety of comics publishers and creators: Zan Christensen, Chip Zdarsky, Erika Moen, Cory Silverberg, C. Spike Trotman, and Shintaro Kago. Each of the panelists has their own approach to sex in regards to how it is related to and portrayed in their work, whether their focus is on sex education, erotica, some combination of the two, or something else entirely. One cultural difference that emerged during the conversation was that while erotic comics are currently seeing a resurgence in North America (Oni Press recently announced a new imprint devoted to sex positive comics, and there have been numerous, highly-successful crowd-funded projects for feminist and queer erotic comics in the last few years), the market for erotic manga in Japan has always been very strong. A very specific set of constraints exist in Japan in regards to the depiction of sex in media, what can and cannot be shown and so on, but the country probably has the most well-established and easily navigable erotic comics scene in the world. Many Japanese creators (including Kago himself) got their start working in erotic media before moving on to other and more mainstream projects. Interestingly, Kago also mentioned that BL isn’t necessarily always recognized as being “erotic” (possibly because its target demographic is women) and so in some ways the genre can actually get away with more than hentai aimed at heterosexual men which, in his experience, seems to come under public scrutiny and fire more quickly and more often.

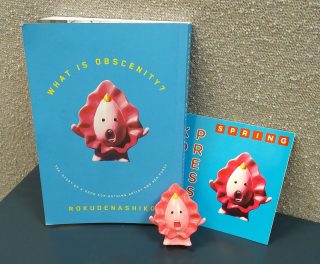

The third panel I attended on Saturday was Rokudenashiko’s Spotlight which was absolutely delightful. After a brief introduction by Rebecca Sullivan, Rokudenashiko began by telling her story of how she came to be a vagina artist and activist and how she was subsequently arrested multiple times. Accompanying Rokudenashiko’s talk was a slide show of some of her artwork, and she brought along some of her small sculptures to show as well, including a remote-controlled “Gundaman.” Much of what she talked about I was already familiar with having read her manga What Is Obscenity? (which I highly recommend), but it was wonderful to see and hear her in person. Just like her work, Rokudenashiko is incredibly charming, cheerful, and funny. The humor and cuteness that Rokudenashiko brings to her manga, illustrations, and sculptures is very deliberate on her part. She noted that many feminist creators dealing with similar subject matter frequently use their art to express their anger and sadness which makes for very heavy work. So instead, Rokudenashiko wanted to do something that was more lighthearted and amusing. It was only after she realized that some people couldn’t laugh and have fun with it that she became more aggressive in her activism efforts, but without ever losing her sense of humor and positivity in her artwork. However, some critics and academics don’t appreciate this, feeling that she’s making too light of a serious subject. Rokudenashiko was very pleased with her reception in North America, saying that the long lines of people waiting to meet her would never happen in Japan where most people are generally too embarrassed to engage so publicly even if they recognize her and are interested in and support what she is doing.

Last year at TCAF I attended a panel on manga translation which was fascinating, so when I saw the “Translation” panel listed as part of the programming for 2016 I was immediately interested. This year the panel was moderated by Deb Aoki and featured three panelists: Jocelyne Allen, who translates from Japanese to English, Samuel Leblanc, a Canadian creator primarily working in French whose debut comic Perfume of Lilacs was released in English, and the French creator Boulet who (after a disastrous attempt to work with fans) currently translates his own comics into English. Leblanc was able to work directly with his translator and was able to provide feedback on the translation being done whereas Allen very rarely had the opportunity to be in contact with the creators of the works that she was translating. Although each of the panelists brought their own perspective to the conversation, they all agreed that capturing the appropriate tone and style is one of the most difficult things about translation. That and the fact that it’s nearly impossible to make everyone happy with a translation since so many people are invested in it each for their own reasons, whether it be the original creators, the translators, the publishers, or the readers. Lately however, the trend in comics translation seems to err on the side of the artists’ original choices and intent rather than focusing on localization. There are also different types of translation work which require different sets of skills—translating comics isn’t the same as translating prose literature which isn’t the same as translating technical manuals and so on. One thing that can be particularly challenging for comics translation is that the amount of space allowed for text is often limited. The visual element of the comics can have a great impact on the interpretation of a scene and the resulting word choices as well.

On Sunday I was only able to make it to two panels before heading back home. One of the reasons that I enjoy TCAF so much is that it is an incredibly queer-friendly and queer-positive event, both in the exhibitor areas and in its programming. I was especially looking forward to “Queer Science Fiction and Fantasy,” a panel moderated by Melanie Gillman and featuring Megan Rose Gedris, Jeremy Sorese, Dylan Edwards, Andrew Wheeler, Taneka Stotts, and Gisele Jobateh, all of whom are queer creators of queer comics. Historically, queerness in speculative fiction has been relegated to subtext, but more and more that queerness is becoming increasingly obvious and in some cases is even the focus of a work. Speculative fiction allows for the creation and exploration of worlds that reflect upon current societal issues while showing what other possibilities could exist. Several of the panelists mentioned that when they were growing up speculative fiction provided some of the only representation of queerness that they saw in media, such as alternative relationship and social structures or a wider variety of genders and sexualities. Frequently, it was the non-human characters that they were most easily able to identify with and the inherent queerness of speculative fiction helped them to understand and discover their own identities. (All of this rings very true for me, too.) Webcomics and self-publishing efforts have been huge in changing the landscape of the comics market to the point where more mainstream publishers, which are slow to evolve and risk-averse, are now reaching a tipping point where queer content isn’t being automatically rejected. Deliberately, intentionally, and unquestionably queer speculative fiction is an evolving genre. Whether they mean to or not, independent creators are currently defining the expectations, tone, language, and tropes that are being set for queer representation in comics and what queer speculative fiction looks like.

The final panel I attended on Sunday was “Discussing Diversity (More or Less)” which was moderated by David Brothers. The panelists included Karla Pacheco, Cathy G. Johnson, Gene Luen Yang, Anne Ishii (one of the marvelous people behind Massive Goods), Ant Sang, and Bill Campbell. Diversity is a huge buzzword right now and not just in comics and other media. (Even my workplace is trying to focus on issues surrounding diversity, so it’s something I’m thinking about a lot these days.) In many of the conversations taking place in North America, diversity is often broadly defined as being non-straight/white/male which, in reality, is actually most of the world. The panel’s incredibly refreshing approach to discussing diversity was simply to talk about it as if was normal, because it is, rather than treating it as an exception or something unusual. As the panelists spoke about their own personal experiences and work, several common themes emerged, probably the most important being that there absolutely is a market, and a need, for diverse media. Though it can be a deliberate initiative, diversity in comics is a natural and often unintentional extension of creators’ own lives, interests, identities, and perspectives. There is also a distinct difference between providing more diverse representation in mainstream media and allowing a more diverse pool of creators to participate and express themselves within that context. While it might be a starting place, non-straight/white/male characters being written by straight/white/male creators sets an extremely low bar in terms of diversity. New voices and perspectives are just as critical if not more so in order to ensure that the comics market remains healthy as it continues to grow and evolve.

Sadly, because the kidling was getting cranky, I had to leave the festival before the food in comics panel which I was really hoping to attend. I was sad to miss most of the “What Women Want” panel’s third year, too. But I have come to realize that even if I wasn’t leaving “early,” it is impossible to see and experience everything that TCAF has to offer and choices must be made. Actually, this is something that I’ve known since the very beginning. There are always going to be panels I miss or that conflict with one another, and after the fact I’m always going to end up discovering comics that I would have been interested in and creators that I wish I had known about. But even so, that doesn’t detract from my overall enjoyment of the event and I am tremendously happy with what I was able to attend this year. TCAF is such a truly wonderful festival. As always, I’m already looking forward to and planning for my trip to Toronto for the event next year.