|

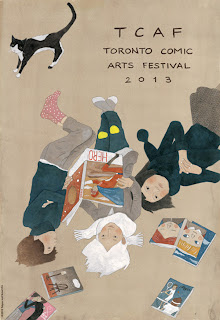

| © Taiyo Matsumoto |

I first learned about the Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF) in 2011 when Usamaru Furuya and Natsume Ono were invited to the event as featured guests. (As a side note: translations of their diary manga from the trip are included in the 2013 TCAF program guide.) It took me two years to finally work up the courage to attend TCAF myself and get my passport in order. 2013 marked TCAF’s tenth anniversary. This year’s festival featured over four hundred creators from nineteen different countries, including mangaka Taiyo Matsumoto and Gengoroh Tagame. While there were festival events throughout May, TCAF 2013’s main exhibition took place on Saturday, May 11th and Sunday, May 12th.

In order to keep the cost of the trip as low as possible, I crossed over the border into Canada from Michigan early Saturday morning along with my good friend Traci (who contributed a guest post here at Experiments in Manga not too long ago.) I arrived in Toronto in time to see The World of Taiyo Matsumoto, an exhibition at The Japan Foundation featuring original artwork by Matsumoto (creator of Blue Spring, Tekkon Kinkreet, GoGo Monster, and the recently released Sunny.) Matsumoto himself was in attendance for a special interview and artist’s talk. The turnout was huge—standing-room only and some people even had to be turned away. Matsumoto admitted that he never expected so many people to turn out to see him and that he was greatly honored. The event and exhibit, which focused on Matsumoto’s artwork, were marvelous. I certainly learned quite a bit: Matsumoto and Santa Inoue (creator of Tokyo Tribes) are cousins and they regularly talk about manga and help each other out; Tekkon Kinkreet was originally intended to be six volumes long, but ended after three since it wasn’t popular enough to continue (although Matsumoto said that he is satisfied with its conclusion and has no desire to revisit the story); in the beginning, Matsumoto was actually reluctant and even resentful working on Ping Pong, which became his breakout manga; and while Matsumoto has always been an innovative artist, more recent developments in printing technology have allowed him to experiment with different drawing materials and techniques, moving even further away from the use of screentone.

|

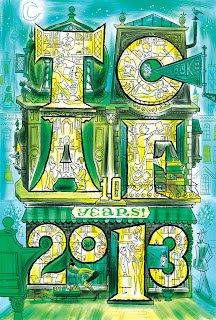

| © Maurice Vellekoop |

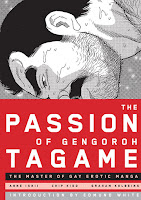

From The Japan Foundation, I headed over to the spotlight on Gengoroh Tagame, a highly influential gay manga artist. Joining Tagame were Anne Ishii, Chip Kidd, and Graham Kolbeins to celebrate Tagame and his work and to discuss the recent release of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, which they all had a hand in bringing into being. The panelists were all very enthusiastic and had a great senses of humor. Because of this, the spotlight was engaging and entertaining in addition to being informative. Apparently, there was a rumor that Tagame did not want his work translated into English. He assured us all that this was not true. In fact, he was surprised that it took until now for a collection of his manga to be released in English. It is possible that the rumor may have had a chilling effect on the licensing of Tagame’s materials. Like so many other people (myself included), he is very excited about the publication of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame. He is also unbelievably happy that others share enjoyment in his fantasies. Tagame is unusual in that very few gay manga artists in Japan are able to make their living on their artwork alone, most hold at least a second job. The panel ended with a very interesting conversation about gay manga and bara (manga typically geared towards gay men) and boys’ love and yaoi (manga typically geared towards women.) It’s difficult to generalize about the genres and the distinction between them isn’t always as clear as some people claim or would like; there can be considerable grey area, crossover, and overlap between the two. For a time, yaoi served as an outlet for gay manga before bara became more publicly acceptable and gay manga magazines were established. Tagame actually started out by submitting his work to yaoi magazines when he was eighteen and he continues to have a large number of female fans. In line for his signing after the talk were people of all (adult) ages, genders, and sexualities, which was wonderful to see.

After having my copy of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame signed, Traci and I met up together again. We made our way down to The Beguiling Books & Art which is an astounding, award-winning comics store. If you find yourself in Toronto, I highly recommend stopping by The Beguiling. It has new comics, old comics, out-of-print comics, mainstream comics, alternative comics, independent comics, domestic comics, international comics (including the largest selection of manga that I’ve ever seen in one place), and more, more, more. And since the shop was across the street from Koreatown, Traci and I took the opportunity to chow down on some delicious Korean food before heading over to Church on Church to catch the tail end of the TCAF Queer Mixer. Unfortunately, we missed the reception and artist talks, but we still were able to see the exhibit Legends: The Gay Erotic Art of Maurice Vellekoop and Gengoroh Tagame which was well worth the trek across town. (Honestly, I was more interested in the art than I was in the mixer itself, anyways.) On a more personal note, I have never had the opportunity to walk around a queer neighborhood before. It was an awesome and somewhat surreal experience for me; it made me very happy just to be in the Church Wellesley Village area.

On Sunday, I attended the Comics Editing International panel which brought together four comics editors from different countries and backgrounds: Thomas Ragon from Dargaud (the oldest comics publisher in France), James Lucas Jones from Oni Press, Mark Siegel from First Second Books, and Hideki Egami from IKKI/Shogakukan. The group talked about the similarities and differences between their work as editors and the comics markets in their countries. The panel was fascinating. I love IKKI manga, and so was very excited to hear editor-in-chief Egami speak. IKKI is different from most magazines in Japan; it appeals to mangaka who want more control over their work and artistic vision as well as those who want to escape the factory-like system associated with so many of the other magazines. Egami mentioned that the manga industry in general is in decline in Japan, and so publishers are beginning to look outside of the country more and more where once they were almost exclusively focused on the domestic market. IKKI has even started to experiment by publishing left-to-right comics with horizontal text, hoping that they will be more easily adapted, translated, and distributed in other countries. I also attended Sunday’s Queer Comics panel which featured Zan Christensen (who is utterly delightful), Erika Moen, Justin Hall, Chip Kidd, and Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez. They talked about queer comics specifically and the representation of queer characters in comics in general, with a particular emphasis on non-binary and fluid sexualities and genders, which I personally appreciated. It was a great group and a great discussion.

|

| My very small, TCAF haul |

For the most part, I intentionally flew under the radar while at TCAF. I saw several of my fellow manga lovers around (Deb Aoki, Brigid Alverson, and Jocelyne Allen, just to name a few) and I know that there were even more of us there, too, but I tend to keep to myself and didn’t seek anyone out. I did, however, wander around the exhibitors’ area for a bit. Because I promised that I would, I made a point to introduce myself to the wonderful ladies of Chromatic Press and Tokyo Demons, which is one of my more recent obsessions. (I had been invited to the Chromatic Manga Mixer on Friday night, but I sadly wasn’t in town yet.) I also chatted with Alex Woolfson about Artifice and The Young Protectors and stopped by Jess Fink‘s table long enough to awkwardly profess my love for her work. Ryan Sand’s new publishing effort Youth in Decline made it’s official debut at TCAF, so I picked up a copy of the first issue of Frontier to show my support. One of the best things about TCAF, other than the chance to see so many fantastic artists who I already follow all in one place (and there were a lot of them there), was the opportunity to discover creators who I wasn’t previously aware of. This is how I ended up bringing home Andrew Fulton‘s minicomic Pubes of Fire, Pubes of Flame which continues to greatly amuse me.

I really do not do well in unstructured, social settings; simply attending TCAF was a huge deal for me and a tremendous personal achievement. I largely consider my first TCAF experience to be a success. I am very happy to report that Traci and I both had a phenomenal time. After only a few hours of being there, I was already making plans for a return visit for next year’s show. Seriously, TCAF is amazing. There was so much going on that I had to make some extremely tough decisions about which programs to attend over others. I saw a ton of incredible work from incredible creators from all over the world and I still feel like there was more that I didn’t get to see. So next year, I’ll be showing up no later than the Friday before the main exhibition and preferably earlier. I’ll be scheduling more time to spend exploring every nook and cranny of the exhibitors’ area. I’ll also be carrying around some snacks with me during the festival; I was so busy and engaged by the programming and exhibits that I actually forgot to eat for most of the day. Next year, I hope to have the guts to actually introduce myself to everyone and maybe even socialize a bit more, too. (Please do not be offended if I didn’t say hello to you this year!) As long as there’s a TCAF, you can expect me to be there.