My News and Reviews

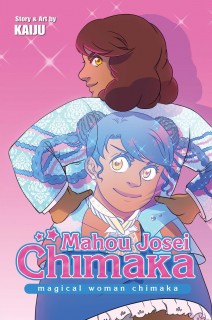

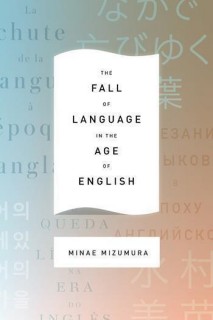

Two in-depth reviews were posted at Experiments in Manga last week. The first was of The Fall of Language in the Age of English by Minae Mizumura, a fascinating and immensely readable work of nonfiction about literature and language. (Mizumura’s A True Novel also greatly impressed me, so at this point I’ll basically read anything written by her; if only more would be translated!) The second review was of KaiJu’s Mahou Josei Chimaka, one of Chromatic Press’ most recent paperback releases and a delightfully entertaining parody of and a loving homage to the magical girl genre. The comic is playful, humorous, and a lot of fun.

Elsewhere online: The Toronto Comic Arts Festival has announced its first round of featured guests. The list includes Rokudenashiko, whose manga What Is Obscenity? will be making its English-language debut at the festival. Bruno Gmünder will be bringing The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame back into print later this year in a newly revised and expanded edition. Ryan Holmberg’s most recent What Was Alternative Manga? includes a translation of a discussion between Hayashi Seiichi and Sasaki Maki. And on Twitter, Digital Manga is hinting at a launch of another classic manga Kickstarter, only this time it won’t be Tezuka.

Quick Takes

Bug Boys, Volume 1: Welcome to Bug Village by Laura Knetzger. Although I’ve read and enjoyed a few of Knetzger’s short autobiographical comics, I picked up Bug Boys more by chance than anything else. I’m so glad that I did, because I’m absolutely loving this comic. Originally a series of self-published mini-comics, the first book was recently released by Czap Books. The hefty volume collects all of the previously released Bug Boys comics in addition to new, never-before-seen content. The comics are mostly black-and-white, but Knetzger also occasionally uses color. The story follows Rhino-B and Stag-B, two young beetles and best friends living in Bug Village, as they grow up, go on adventures, and explore their world. It’s all incredibly cute and touching, even when the two of them are dealing with some fairly big, weighty issues. Friendly enough for children, but also thoroughly enjoyable for adults, Bug Boys is one of the most wonderfully delightful and charming comics that I’ve read in a very long time. I’ll definitely be keeping an eye out for more of the series and for more of Knetzger’s work.

Bug Boys, Volume 1: Welcome to Bug Village by Laura Knetzger. Although I’ve read and enjoyed a few of Knetzger’s short autobiographical comics, I picked up Bug Boys more by chance than anything else. I’m so glad that I did, because I’m absolutely loving this comic. Originally a series of self-published mini-comics, the first book was recently released by Czap Books. The hefty volume collects all of the previously released Bug Boys comics in addition to new, never-before-seen content. The comics are mostly black-and-white, but Knetzger also occasionally uses color. The story follows Rhino-B and Stag-B, two young beetles and best friends living in Bug Village, as they grow up, go on adventures, and explore their world. It’s all incredibly cute and touching, even when the two of them are dealing with some fairly big, weighty issues. Friendly enough for children, but also thoroughly enjoyable for adults, Bug Boys is one of the most wonderfully delightful and charming comics that I’ve read in a very long time. I’ll definitely be keeping an eye out for more of the series and for more of Knetzger’s work.

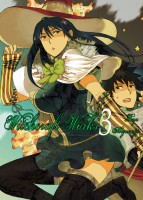

Butterflies, Flowers, Volume 1 by Yuki Yoshihara. Once wealthy aristocrats, the members of the Kuze family have fallen on hard times. They no longer have any servants and have instead become the masters of a soba noodle shop. Choko is now searching for separate employment, only discovering after the fact that her new boss, Masayuki Domoto, is the son of the family’s old chauffeur. Butterflies, Flowers is a somewhat peculiar romantic comedy that’s hard to take seriously. Granted, I don’t think that the manga is really intended to be taken seriously. And I’ll admit, the first volume of the manga made me laugh on several occasions. The power dynamics in Butterflies, Flowers are all over the place, so it’s difficult to know what to expect from one page to the next, especially where Choko and Domoto are involved. At first Choko doesn’t have much confidence—working in an office is a new experience for her—but every once in a while she’ll take charge of the situation. As for Domoto, he frequently switches from being an overbearing and demanding boss to being completely subservient to the woman and family that used to employ his father.

Butterflies, Flowers, Volume 1 by Yuki Yoshihara. Once wealthy aristocrats, the members of the Kuze family have fallen on hard times. They no longer have any servants and have instead become the masters of a soba noodle shop. Choko is now searching for separate employment, only discovering after the fact that her new boss, Masayuki Domoto, is the son of the family’s old chauffeur. Butterflies, Flowers is a somewhat peculiar romantic comedy that’s hard to take seriously. Granted, I don’t think that the manga is really intended to be taken seriously. And I’ll admit, the first volume of the manga made me laugh on several occasions. The power dynamics in Butterflies, Flowers are all over the place, so it’s difficult to know what to expect from one page to the next, especially where Choko and Domoto are involved. At first Choko doesn’t have much confidence—working in an office is a new experience for her—but every once in a while she’ll take charge of the situation. As for Domoto, he frequently switches from being an overbearing and demanding boss to being completely subservient to the woman and family that used to employ his father.

Terra Formars, Volumes 5-8 written by Yu Sasuga and illustrated by Ken-ichi Tachibana. It’s been a while since I’ve read any of Terra Formars, but it wasn’t too difficult to pick it up again where I left it—even considering the various plot twists, the series is pretty easy to follow and tends to be fairly action-oriented. By far the best thing about Terra Formars for me are the over-the-top battles between super-powered combatants. Not only have humans been crossed with insect genetics, there are examples of those who have been crossed with birds, mammals, aquatic creatures, plants, and even bacteria, giving the individuals a wide variety of incredible abilities. Realistic? Perhaps not, but the resulting battles are epic. (Surprisingly, Terra Formars has actually taught me quite a few things about plants and animals.) The political maneuvering back on Earth, while being portrayed in a very dramatic fashion, frankly doesn’t interest me that much. However, it is that drama that largely propels what little story the series has. It also means that the modified humans end up having to fight each other in addition to the Martian inhabitants.

Terra Formars, Volumes 5-8 written by Yu Sasuga and illustrated by Ken-ichi Tachibana. It’s been a while since I’ve read any of Terra Formars, but it wasn’t too difficult to pick it up again where I left it—even considering the various plot twists, the series is pretty easy to follow and tends to be fairly action-oriented. By far the best thing about Terra Formars for me are the over-the-top battles between super-powered combatants. Not only have humans been crossed with insect genetics, there are examples of those who have been crossed with birds, mammals, aquatic creatures, plants, and even bacteria, giving the individuals a wide variety of incredible abilities. Realistic? Perhaps not, but the resulting battles are epic. (Surprisingly, Terra Formars has actually taught me quite a few things about plants and animals.) The political maneuvering back on Earth, while being portrayed in a very dramatic fashion, frankly doesn’t interest me that much. However, it is that drama that largely propels what little story the series has. It also means that the modified humans end up having to fight each other in addition to the Martian inhabitants.