Creator: Yeon-sik Hong

Creator: Yeon-sik Hong

Translator: Hellen Jo

U.S. publisher: Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 9781770462601

Released: June 2017

Original release: 2012

Awards: Manhwa Today Award

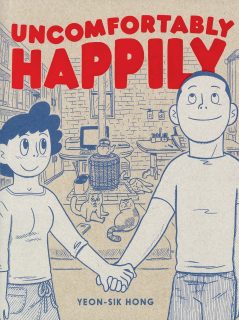

Lately it seems as though there has been something of a renaissance or Korean literature in English translation. Korean comics haven’t yet experienced quite the same kind of resurgence, but they do continue to be licensed and translated. One of the most recent and notable manhwa releases in English is Yeon-sik Hong’s aptly named Uncomfortably Happily. Previously published in France in 2013 under the title Historie d’un Couple (History of a Couple), Uncomfortably Happily was originally released in Korea in two volumes in 2012 where it won the Manhwa Today Award. Drawn and Quarterly’s English-language edition of the work collects the entirety of Uncomfortably Happily in a single volume and features a translation by Hellen Jo, an accomplished comics creator and illustrator in her own right. The volume also includes a personal essay by Jo. Uncomfortably Happily is Hong’s first major personal work, a memoir of the short time he and his wife lived in the Korean countryside. Prior to its release, Hong was predominantly involved in commercial creative projects.

Yeon-sik Hong and Sohmi Lee are recently married and looking for a new home; their current apartment is on loan to Yeon-sik from one of his previous publishers and it’s past time that they move on. Since they’ll need to leave anyway, the couple decides to take the opportunity to find a place that’s more suited to their needs. Somewhere quiet and less complicated, congested, and expensive than city life in Seoul; somewhere they can both focus on their creative work. Eventually the two become enamored with a house and a bit of land for rent on the top of a mountain in rural Pocheon. With the clean air, beautiful countryside, and calm environment it seems like the perfect place for them–at least at first. Yeon-sik, Sohmi, and their three cats make the move only to discover that living in the country brings along with it its own sorts of challenges. But despite the isolation, inadequate public transportation, confrontations with hostile hikers, inclement weather, and encroaching development, they slowly build a home for themselves. It can be difficult at times, though, and some things never really change–financial hardship, personal anxieties, and looming deadlines don’t simply disappear and it’s just as easy to find distractions in the countryside as it is in the city.

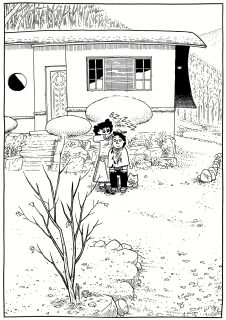

Though I currently live in a more urban environment, I grew up and have spent most of my life in a very rural area. In Uncomfortably Happily, Hong captures beautifully what it is like to live in the country, both the good and the bad, the satisfaction and the stress. The volume’s chapters are divided by season, the narrative perfectly conveying the rhythms of the natural world and the lifestyle that is so closely dependent upon those rhythms, including the winters that seem to last forever with no relief in sight. Hong’s style of illustration is relatively simple but the attention given to the detail of the land- and cityscapes establish a real sense of place. In addition to the external world, the visuals in Uncomfortably Happily also reveal Hong’s internal mindscapes and imaginative fantasies. Though the subject matter can often be quite serious, Hong takes a charming and lighthearted approach. The small family (animals included) frequently break into musical numbers and Hong’s psyche manifests on the page in both amusing and affecting ways. But while humor is generally present in Uncomfortably Happily, the manhwa is also a sincere and honest work.

Though I currently live in a more urban environment, I grew up and have spent most of my life in a very rural area. In Uncomfortably Happily, Hong captures beautifully what it is like to live in the country, both the good and the bad, the satisfaction and the stress. The volume’s chapters are divided by season, the narrative perfectly conveying the rhythms of the natural world and the lifestyle that is so closely dependent upon those rhythms, including the winters that seem to last forever with no relief in sight. Hong’s style of illustration is relatively simple but the attention given to the detail of the land- and cityscapes establish a real sense of place. In addition to the external world, the visuals in Uncomfortably Happily also reveal Hong’s internal mindscapes and imaginative fantasies. Though the subject matter can often be quite serious, Hong takes a charming and lighthearted approach. The small family (animals included) frequently break into musical numbers and Hong’s psyche manifests on the page in both amusing and affecting ways. But while humor is generally present in Uncomfortably Happily, the manhwa is also a sincere and honest work.

Uncomfortably Happily is a straightforward yet layered story of the day-to-day life of a newlywed couple going through a major transition in their life. There is the move to the countryside itself and all that entails, but Uncomfortably Happily is also the story about Hong’s emotional and mental turmoil as he struggles with professional and personal insecurities. At the beginning of Uncomfortably Happily Hong is already approaching burnout and the potential for a breakdown doesn’t seem to be very far behind; meanwhile Lee is making tremendous progress in her career as a picture book illustrator. It was bound to happen eventually regardless of location, but Hong having to confront and come to terms with his own abilities and limitations, wants and needs while living on a secluded mountaintop has a certain poetic appropriateness to it. While Hong’s particular situation and psychological journey are certainly unique, the themes explored in the manhwa are universal; Uncomfortably Happily is an engrossing and immensely relatable work.

Thank you to Drawn & Quarterly for providing a copy of Uncomfortably Happily for review.