Author: Han Kang

Author: Han Kang

Translator: Deborah Smith

U.S. Publisher: Hogarth Press

ISBN: 9781101906729

Released: January 2017

Original release: 2014

Awards: Manhae Literary Prize

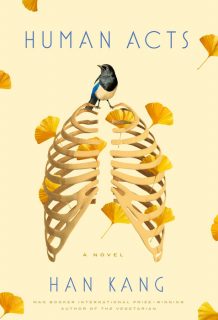

Over the last few years South Korean novelist Han Kang has gained a fair amount of international attention. Of particular recent note, her second novel to be translated into English, The Vegetarian (which I’ve been meaning to read for quite some time now), was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in 2016 after being met with great acclaim. Kang isn’t a stranger to awards–her work, while at times controversial, is well-regarded and has earned her many honors and accolades both in South Korea and abroad. Human Acts is Kang’s third novel to receive an English translation. The book was originally published in Korea in 2014 (under a title that more closely translates as The Boy Is Coming) and won Kang the Manhae Literary Prize. Deborah Smith’s English translation of and accompanying introduction to Human Acts was first published in Great Britain in 2016 and is scheduled to be released in the United States in early 2017.

After the assassination of South Korean president Park Chung-hee in 1979, the political climate of the country became increasingly perilous. The student demonstrations calling for democracy and the protests against the government which began during Park’s rule when he implemented authoritarian policies and martial law continued even after his death. In 1980, in the southern city of Gwanju, one such demonstration was engulfed in violence when a group of citizens supporting the students’ efforts was attacked and killed by government forces. The protest in Gwanju quickly escalated into an uprising involving thousands. The incident only lasted a few days–ultimately the civil militias were defeated by the government troops–but the uprising and accompanying massacre would deeply impact South Korea and its people for decades to come, leaving a wound that has yet to completely heal.

Human Acts focuses on the aftermath of the Gwanju Uprising and the personal costs, pain, and suffering of the people involved. The novel unfolds in seven parts told from seven different perspectives. It begins in the midst of the uprising itself in 1980 and ends in 2013 with its lingering influence. Human Acts opens with the story Dong-ho, a middle school student working in a gymnasium which had been hastily converted into a temporary morgue in order to accommodate the tremendous number of casualties. There he helps to care for and identify the bodies. After he himself is killed during the uprising, Dong-ho becomes the touchstone which ties the disparate parts of the novel together. In addition to Dong-ho, Human Acts contains the accounts of the soul of his friend who also lost his life, two of the women who worked in the morgue with him, a protestor who witnessed his death and who was later arrested, imprisoned, and tortured, his mother, and the writer who retells their stories.

Human Acts is a beautifully written novel, the translation is elegant and at times even poetic, but the subject matter is horrific and tragic and Kang doesn’t shy away from that fact. The story, based on truth, is filled with death, brutality, and violence. Human Acts is extraordinary though it certainly isn’t light reading; it can be a very difficult, affecting, and haunting read. The text slips in and out of a second-person narrative which draws the reader directly into the story. The technique is surprisingly effective and disconcerting, helping to turn the novel into something that’s akin to both a eulogy and a denunciation. While Human Acts focuses on a specific historical event, its themes are universal, exploring the lasting changes that the past has on the present and how people as individuals cope with the trauma that has been experienced. Human Acts is an intensely personal, political, powerful, and devastating work and is honestly one of best novels that I have read in a long while.

Thank you to Hogarth Press for providing a copy of Human Acts for review.