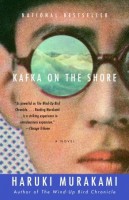

Author: Haruki Murakami

Author: Haruki Murakami

Translator: Philip Gabriel

U.S. publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

ISBN: 9781400079278

Released: January 2006

Original release: 2002

Awards: World Fantasy Award

Haruki Murakami is an international best-selling author and one of the most recognizable Japanese novelists currently writing worldwide. Therefore, I find it somewhat surprising that I actually haven’t read much of his work. Before picking up Kafka on the Shore I had only read two of his books—1Q84 and Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche—in addition to a small selection of essays and interviews. 1Q84 was my introduction to Murakami; it was both an incredibly frustrating and invigorating experience. I loved parts of the novel but strongly disliked others. 1Q84 probably wasn’t the best place to start reading Murakami, and so I’ve been meaning to give another one of his novels a try. I settled on Kafka on the Shore, originally published in Japan in 2002, for several reasons. It’s one of Murakami’s best-known works. Philip Gabriel’s 2005 English translation won the World Fantasy Award. The novel’s young protagonist basically runs away to a library. But mostly, I wanted to read Kafka on the Shore for the sake of one character, Oshima, with whom I happen to share quite a bit in common.

Fifteen-year-old Kafka Tamura, though that’s not his real name, has just run away from home. He leaves behind his father in Tokyo just as his mother and sister left the two of them behind more than a decade ago. Kafka’s plan is simple—travel to a faraway town and make a place for himself in a library. That’s how he finds himself in Takamatsu, over four hundred miles away from the home, father, and life that he wants to escape. There he seeks out the privately owned Komura Memorial Library where meets Oshima, an assistant at the library who takes Kafka under his wing. Meanwhile, strange events are unfolding around Kafka and the people in his life. Back in Tokyo, a man by the name of Nakata with the ability to talk to cats finds himself pulled into Kafka’s story. Though the two have never met they share a strange connection with each other that neither of them are entirely aware of or expected.

The chapters in Kafka on the Shore alternate between Kafka and Nakata’s individual journeys. Kafka’s chapters are written in first-person present, giving them a very intimate and immediate perspective, while Nakata’s are written in third-person past, creating more distance. At first the two stories seem to be completely unrelated, but as Kafka on the Shore develops the tales steadily draw towards one another and connect in shocking ways. Kafka and Nakata’s paths never directly cross but they do influence each other and those of the people around them. Ideas, concepts, and turns of phrase, not to mention actions and their consequences, echo throughout the novel, tying seemingly disparate events together into a cohesive whole. There is a lot of loneliness in Kafka on the Shore. The characters are searching and reaching out for these sorts of connections and relationships, both consciously and subconsciously. They are individuals yearning to find what is missing from themselves and from their lives, often disregarding time and reality in the process.

Much as with 1Q84, there were parts of Kafka on the Shore that I adored and other parts that I found immensely frustrating. In general, I preferred the earlier novel over its later developments. For me, Kafka on the Shore worked best when it was more firmly grounded in reality with hints of the unexplainable, mysterious, and strange rather than the other way around. As the novel progresses it becomes more confusing and dreamlike. That in and of itself isn’t problematic, but towards the end of Kafka on the Shore Murakami begins introducing bizarre elements seemingly out of nowhere that do very little to develop the plot or the characters. Readers looking for closure from Kafka on the Shore may be disappointed as there are plenty of threads left unresolved by the time the novel reaches its conclusion. Despite my frustrations with Kafka on the Shore I am glad that I read the novel. I appreciated the importance giving to books and the influence of music; I found the characters intriguing; and although the story goes a little off the rails, I liked Kafka’s peculiar journey of discovery and coming of age.