Editor: Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington

Editor: Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington

Publisher: Viz Media

ISBN: 9781421571744

Released: September 2014

Phantasm Japan: Fantasies Light and Dark from and about Japan, edited by Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington, is the second anthology of short fiction curated specifically for Haikasoru, the speculative fiction imprint of Viz Media. Phantasm Japan, published in 2014, is a followup of sorts to the 2012 anthology The Future is Japanese. A third anthology in the loosely-related series, Hanzai Japan, is currently being complied. I rather enjoyed The Future Is Japanese and so was looking forward to the release of Phantasm Japan. The anthology collects twenty-one pieces of short fiction, including an illustrated novella, from seventeen creators in addition to the two introductory essays written by the editors. Most of the stories are original to the collection, although a few of the translated works were previously published in Japan. Much like The Future Is Japanese, Phantasm Japan promised to be an intriguing collection.

With a title like Phantasm Japan I had anticipated an anthology inspired by yokai and Japanese folklore. And while the volume does include such tales—Zachary Mason’s “Five Tales of Japan” (tengu and various deities), James A. Moore’s “He Dreads the Cold” (yuki-onna), Benjanun Sriduangkaew’s “Ningyo” (mermaids and other mythological beings)—it incorporates a much broader variety of stories as well. The fiction found in Phantasm Japan is generally fairly serious in nature and tone and all of the stories tend to have at least a touch of horror to them, but they range from historical fiction to science fiction and from tales of fantasy to tales more firmly based in reality. Pasts, presents, and futures are all explored in Phantasm Japan. The authors of Phantasm Japan are as diverse as their stories. Some make their homes in Japan while some hail from the Americas, Europe, or other parts of Asia. Many are established, award-winning writers while others are newer voices. In fact, Lauren Naturale’s “Her Last Appearance,” inspired in part by the life of kabuki actor Kairakutei Black, marks her debut as a published author of fiction. I also personally appreciated the inclusion of both queer authors and queer characters in the anthology.

Other than being a collection of fantastical stories, there isn’t really an overarching theme to Phantasm Japan. However, some of the works do explore similar concepts, but use wildly different approaches and settings. In addition to the stories influenced by traditional lore, like “Inari Updates the Map of Rice Fields” by Alex Dally MacFarlane, there are those that reflect more contemporary concerns like Tim Pratt’s “Those Who Hunt Monsters” which mixes online dating, fetishism, and yokai. Ghost of various types make appearances throughout Phantasm Japan, from the supernatural haunting of Seia Tanabe’s “The Parrot Stone” to the biohazard-induced hallucinations of Sayuri Ueda’s “The Street of Fruiting Bodies.” Joseph Tomaras’ “Thirty-Eight Observations of the Self” is in part reminiscent of stories about living ghosts. Possessions are seen multiple times in the volume as well. In “Scissors or Claws, and Holes” by Yusaku Kitano, creatures are intentionally invited into a person’s body in order to exchange memories for visions of the future while in Jacqueline Koyanagi’s Kamigakari a consciousness is shared by a man and something that isn’t human as a result of an accident.

Other than being a collection of fantastical stories, there isn’t really an overarching theme to Phantasm Japan. However, some of the works do explore similar concepts, but use wildly different approaches and settings. In addition to the stories influenced by traditional lore, like “Inari Updates the Map of Rice Fields” by Alex Dally MacFarlane, there are those that reflect more contemporary concerns like Tim Pratt’s “Those Who Hunt Monsters” which mixes online dating, fetishism, and yokai. Ghost of various types make appearances throughout Phantasm Japan, from the supernatural haunting of Seia Tanabe’s “The Parrot Stone” to the biohazard-induced hallucinations of Sayuri Ueda’s “The Street of Fruiting Bodies.” Joseph Tomaras’ “Thirty-Eight Observations of the Self” is in part reminiscent of stories about living ghosts. Possessions are seen multiple times in the volume as well. In “Scissors or Claws, and Holes” by Yusaku Kitano, creatures are intentionally invited into a person’s body in order to exchange memories for visions of the future while in Jacqueline Koyanagi’s Kamigakari a consciousness is shared by a man and something that isn’t human as a result of an accident.

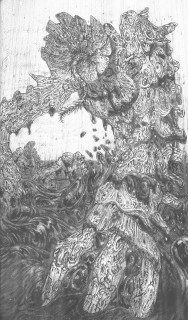

One of the recurring themes that I found particularly appealing in Phantasm Japan was the power of memories and stories to shape, create, define, and redefine reality. In Gary A. Braunbeck’s “Shikata Ga Nai: The Bag Lady’s Tale,” a tailor from a Japanese-American internment camp is responsible for passing on centuries worth of history. In “The Last Packet of Tea” by Quentin S. Crisp, an author struggles to write one last story. Project Itoh’s “From Nothing, With Love” (which re-convinced me that I need to read everything that he has written) is about a very specific cultural touchstone and the life that it has taken on. As with any short story collection, some of the stories are stronger than others and different stories will be enjoyed by different readers. Some contributions to Phantasm Japan are readily accessible to just about anyone, such as Nadia Bulkin’s “Girl, I Love You” and Miyuki Miyabe’s “Chiyoko,” but then there are more challenging works like Dempow Torishima’s exceptionally bizarre and grotesque novella Sisyphean. As for me, I enjoyed Phantasm Japan as an anthology. I liked the range and variety in the stories collected, and my reading list has certainly grown significantly because of it.