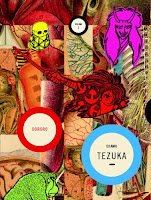

Creator: Osamu Tezuka

Creator: Osamu Tezuka

U.S. publisher: Vertical

ISBN: 9781935654438

Released: August 2012

Original run: 1983-1985

Awards: Kodansha Manga Award

If I recall correctly, the first manga I ever read was likely Osamu Tezuka’s Adorufu ni Tsugu. I first discovered the series while helping a friend track down resources for his senior thesis which largely focused on the Jewish population in Japan during the 1930s and ’40s. (There really does seem to be a manga on just about anything.) Adorufu ni Tsugu was serialized in Japan between 1983 and 1985, earning Tezuka a Kodansha Manga Award in 1986. The series was initially released in English by Viz Media under the title Adolf in five volumes between 1996 and 1997, making it one of the first works by Tezuka to be translated. However, Adolf has long been out of print and difficult to find. I was absolutely thrilled when Vertical announced a two-volume omnibus edition of the series complete with a new translation to be released in 2012. The first volume, Message to Adolf, Part 1 collects the first seventeen chapters of the manga. Needless to say, I was very excited to have the chance to read Adolf again.

While covering the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Sohei Toge, a reporter for the Kyogo News, receives a phone call from his younger brother Isao, who is studying abroad in Germany. Isao is convinced that he is in possession of critical information that could very well topple Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. But by the time Toge is able to meet his brother, he discovers Isao dead and his murder covered up. Suddenly, Toge finds himself pursued by the Gestapo and eventually even the Japanese secret police who believe that Isao has passed along important documents to him. As fate would have it, two young boys in Japan are also caught up in the turmoil and rumors surrounding the documents: Adolf Kaufmann, the son of a Nazi Party member and his Japanese wife, and his best friend Adolf Kamil, the son of German Jews who was born and raised in Japan. Slowly, their stories and destinies become entwined with Toge’s as he continues to search for the reasons behind his brother’s death. With their very lives in danger, the boys’ loyalty to their families and to each other will be repeatedly put to the test.

Although Toge claims to be a secondary character in the tale he is actually one of the primary protagonists in Message to Adolf. A large part of the manga is devoted to him chasing after top secret information and being chased in return. Despite these sections being quickly paced and the political thriller elements and intrigue being exciting (even if Toge’s impressive resilience is somewhat unbelievable), what I find most engaging about Message to Adolf is the relationship between the two young Adolfs. Adolf Kamil is actually one of the most level-headed characters in the entirety of Message to Adolf, Part 1 while Adolf Kaufmann is an impressionable but adorable kid. Tragically, the promise that he makes and keeps in order to protect Kamil is what will eventually drive them apart. Kaufmann’s indoctrination into the Hitler Youth is heartbreaking as he struggles to reconcile what he is being taught with what he knows and believes to be true while his innocence is being shattered. Message to Adolf, Part 1 closes on a particularly heart-wrenching note.

Message to Adolf has a very strong anti-war message. It includes many examples of families and friends that are torn apart by war, fighting, fear, and strict adherence to political dogma. Tezuka incorporates actual events into Message to Adolf, placing the story into historical context; although Message to Adolf is obviously fiction, the tale is convincingly plausible because of this. Some of the more cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s artwork do seem at odds with the more serious and realistic tone of Message to Adolf, but at the same time there are individual panels and layouts that are incredibly striking and effective. The narrative of Message to Adolf is engagingly complex without becoming too confusing. Tezuka has a tendency to introduce side stories which at first appear tangential but are almost always tied back into the main narrative. Although these could come across as coincidences, the story is being told after the fact so it makes sense that it would all be connected. It becomes clear that everything is included for a reason. Personally, I think Message to Adolf is one of Tezuka’s best works.