My News and Reviews

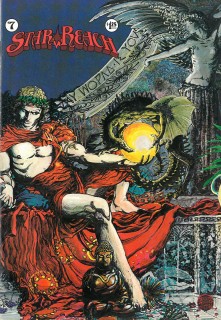

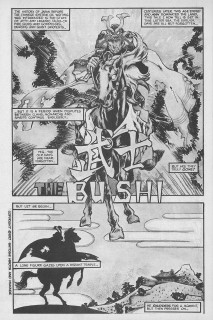

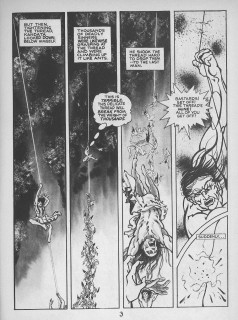

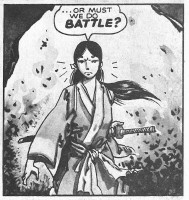

Last week—last Monday, to be exact—Experiments in Manga celebrated its fourth anniversary. I’ve taken to writing what usually ends up being a rather lengthy anniversary post every year in which I reflect on the past three-hundred-sixty-five days, and this year was no different. I also posted a review last week of The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan, Ivan Morris’ classic study of Heian-era Japan and The Tale of Genji. The work was originally published in 1964 and it’s still a great read. Finally, for something a little different, I posted a Spotlight on Masaichi Mukaide who, in the late 1970s, became one of the first Japanese comics artists to be released in English. I rather enjoyed investigating this bit of comics history; I hope other people find it interesting as well.

While working on my random musings about Masaichi Mukaide, I discovered that the three short manga currently believed to be the earliest manga to have been translated into English (Akasegawa Genpei’s “Sakura Illustrated,” Shirato Sampei’s “Red Eyes,” and Tsuge Yoshiharu’s “The Stopcock”) are available online to read digitally. Another interesting piece of reading that I came across last week was Ryan Holmberg’s article on manga, art history, and Seiichi Hayashi at The Comics Journal. Elsewhere online, Sean at A Case Suitable for Treatment looks at some of the latest offerings from Crunchyroll Manga and Justin at Organization Anti-Social Geniuses was able to get some of the manga publishers to weigh in on their approaches to the last pages of manga volumes.

Quick Takes

Food Wars!: Shokugeki no Soma, Volume 1 written by Yuto Tsukuda and illustrated by Shun Saeki. Soma Yukihira wants nothing more than to surpass his father in the kitchen, but his goal of becoming the ultimate chef becomes a little more difficult when his father closes up the family restaurant for three years. In the meantime, Soma is expected to transfer into the most elite and competitive culinary school in Japan. The other students aren’t very welcoming of the son of a low-end family restaurant, so it’s entirely up to the arrogant and uncouth Soma to prove that his cooking is just as impressive as their high-class cuisine. Overall, the artwork in Food Wars is great. The illustrations of the food in particular are incredibly sumptuous. And then there are the reaction shots—those who taste Soma’s cooking often fall into nearly orgasmic ecstasy which is accompanied by highly sexualized imagery. This does include such things as young women being molested by tentacles, which will certainly not appeal to every reader. Personally, I was for the most part rather amused by the ridiculous levels and absurdity of the occasional fanservice.

Food Wars!: Shokugeki no Soma, Volume 1 written by Yuto Tsukuda and illustrated by Shun Saeki. Soma Yukihira wants nothing more than to surpass his father in the kitchen, but his goal of becoming the ultimate chef becomes a little more difficult when his father closes up the family restaurant for three years. In the meantime, Soma is expected to transfer into the most elite and competitive culinary school in Japan. The other students aren’t very welcoming of the son of a low-end family restaurant, so it’s entirely up to the arrogant and uncouth Soma to prove that his cooking is just as impressive as their high-class cuisine. Overall, the artwork in Food Wars is great. The illustrations of the food in particular are incredibly sumptuous. And then there are the reaction shots—those who taste Soma’s cooking often fall into nearly orgasmic ecstasy which is accompanied by highly sexualized imagery. This does include such things as young women being molested by tentacles, which will certainly not appeal to every reader. Personally, I was for the most part rather amused by the ridiculous levels and absurdity of the occasional fanservice.

The Prince of Tennis, Volumes 1-7 by Takeshi Konomi. While recently reading The Princess of Tennis, a memoir written by one of Konomi’s assistants, I came to the realization that I had never actually read any of The Prince of Tennis. The series is one of the most successful and popular sports manga in Japan, growing into a fairly substantial franchise. The Prince of Tennis is an oddly addictive series—I tore through the first seven volumes very quickly—but to some extent it’s also a bit frustrating. There is virtually no story or character development, simply game after game of tennis and middle school trash talk. Some of the most important games, the ones that actually impact the characters’ growth (what little there is) happen almost entirely off-page. All of the players are very strong to begin with, so there hasn’t been much evolution in their performance or skill levels, either. But the various games are interesting and entertaining, if a little over-the-top. There are a lot of good-looking characters of various types, too, which is probably a large part of the series’ appeal. I’m not in a rush to read more, but I did enjoy the first seven volumes.

The Prince of Tennis, Volumes 1-7 by Takeshi Konomi. While recently reading The Princess of Tennis, a memoir written by one of Konomi’s assistants, I came to the realization that I had never actually read any of The Prince of Tennis. The series is one of the most successful and popular sports manga in Japan, growing into a fairly substantial franchise. The Prince of Tennis is an oddly addictive series—I tore through the first seven volumes very quickly—but to some extent it’s also a bit frustrating. There is virtually no story or character development, simply game after game of tennis and middle school trash talk. Some of the most important games, the ones that actually impact the characters’ growth (what little there is) happen almost entirely off-page. All of the players are very strong to begin with, so there hasn’t been much evolution in their performance or skill levels, either. But the various games are interesting and entertaining, if a little over-the-top. There are a lot of good-looking characters of various types, too, which is probably a large part of the series’ appeal. I’m not in a rush to read more, but I did enjoy the first seven volumes.