Author: Tetsu Kariya

Author: Tetsu Kariya

Illustrator: Akira Hanasaki

U.S. publisher: Viz Media

ISBN: 9781421521442

Released: November 2009

Original release: 2005

Awards: Shogakukan Manga Award

At well over one hundred volumes, Oishinbo is one of the most successful and long-running food manga in Japan, winning the Shogakukan Manga Award in 1987. Written by Tetsu Kariya and illustrated by Akira Hanasaki, Oishinbo first began serialization in 1983 and is still ongoing although currently the manga is on indefinite hiatus following a controversy of its depiction of the aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster. Between 2009 and 2010, Viz Media released seven volumes of Oishinbo, A la Carte under its Signature imprint, becoming the first food manga that I ever read. Oishinbo, A la Carte is a series of thematic anthologies collecting chapters from throughout the main Oishinbo manga. Oishinbo, a la Carte: The Joy of Rice was the sixth collection to be released in English in 2009. However, The Joy of Rice was actually the thirteenth volume of Oishinbo, A la Carte to be published in Japan in 2005.

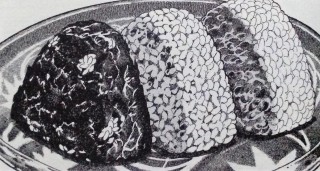

The Joy of Rice collects eight stories and one essay in which rice, an important staple of Japanese diet and cuisine, is featured. In “A Remarkable Mediocrity,” the wrath of a wealthy businessman and gourmand who made his fortune dealing in rice is able to be appeased by the simplest of dishes. “Brown Rice Versus White Rice” examines how people can be mislead even when they make an effort to eat healthily. The structure of rice and how proper storage can make a difference when it comes to cooking it are the focus of “Live Rice.” Yamaoka, Oishinbo‘s protagonist, makes a case against the importation of foreign rice into Japan in “Companions of Rice.” In “The Matsutake Rice of the Sea,” a wager between friends over a rice dish becomes more important than they realize. Kariya opines about the eating manners of Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans in his essay “The Most Delicious Way to Eat Rice.” A debate on the proper way to eat rice is central to “No Mixing” as well. Rice takes a supporting role in “The Season for Oysters,” but once again takes the spotlight in the three-part “Rice Ball Match.”

Because Oishinbo, A la Carte compiles various stories together by theme rather than by chronology, the series can feel somewhat disjointed. Having read nearly all of the Oishinbo, A la Carte collections available in English, for the most part I’ve gotten used to and even expect this, but it seemed to be particularly glaring in The Joy of Rice. From story to story it’s often difficult to anticipate the status of the characters’ relationships with one another and those relationships are often very important to understand. For example, “A Remarkable Mediocrity” is one of the earliest episodes to be found in Oishinbo proper—it’s a little awkward to have the chapter that originally introduced several of the established recurring characters appear so late in A la Carte. Admittedly, the point of Oishinbo, Al la Carte is to highlight specific foods or themes; only a basic understanding of the underlying premise of Oishinbo and of its characters is absolutely necessary. The translation notes help greatly, but it can still make for an odd reading experience.

Because Oishinbo, A la Carte compiles various stories together by theme rather than by chronology, the series can feel somewhat disjointed. Having read nearly all of the Oishinbo, A la Carte collections available in English, for the most part I’ve gotten used to and even expect this, but it seemed to be particularly glaring in The Joy of Rice. From story to story it’s often difficult to anticipate the status of the characters’ relationships with one another and those relationships are often very important to understand. For example, “A Remarkable Mediocrity” is one of the earliest episodes to be found in Oishinbo proper—it’s a little awkward to have the chapter that originally introduced several of the established recurring characters appear so late in A la Carte. Admittedly, the point of Oishinbo, Al la Carte is to highlight specific foods or themes; only a basic understanding of the underlying premise of Oishinbo and of its characters is absolutely necessary. The translation notes help greatly, but it can still make for an odd reading experience.

The Joy of Rice examines the place of rice within Japanese culture and cuisine, addressing both social and scientific aspects of the grain. Like the other volumes in Oishinbo, A la Carte, The Joy of Rice places a huge emphasis on organically and locally produced food, railing against pesticides, herbicides, and the use of antibiotics in agriculture. The series is not at all subtle about the stance it takes, and Yamaoka can frankly be a jerk about it at times. Initially I was hoping that The Joy of Rice would explore the different varieties of rice found and used in Japan, but the volume instead focuses on the significance of rice in the lives of the country’s people—the nostalgia and memories associated with it and the pure enjoyment and complete satisfaction that it can bring—which was ultimately very gratifying. However, my favorite story in The Joy of Rice, “Rice Ball Match,” uses rice to delve into Japanese culinary culture and history as a whole, which was an excellent way to round out the volume, bringing all of the manga’s themes together in one place.