Creator: Masayuki Ishikawa

Creator: Masayuki Ishikawa

U.S. publisher: Kodansha

ISBN: 9781632361905

Released: August 2015

Original release: 2015

I rather enjoyed Masayuki Ishikawa’s short, three-volume manga series Maria the Virgin Witch. Although it was a bit uneven in places, possibly because the series ended sooner than was initially planned (granted, that is my own speculation rather than something that I know for a fact), I liked the series’ quirky characters, historical fantasy, and peculiar mix of humor and more serious philosophical and theological musings. Because Maria the Virgin Witch wrapped up so quickly and left many questions unanswered, I was happy to learn that Maria the Virgin Witch: Exhibition had also been licensed for an English-language release. Originally published in Japan in 2015, Exhibition is a collection of sides stories, a mix of prequels and sequels to the main series. Kodansha Comics released the English-language edition in 2015 as well. It is a relatively slim volume, but I was looking forward to spending a little more time with Maria the Virgin Witch and its characters.

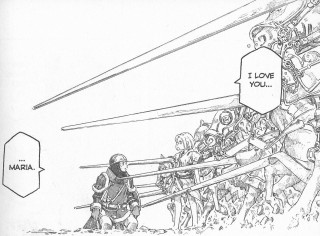

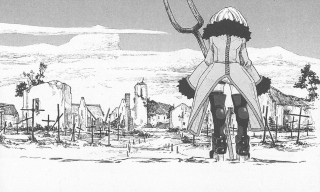

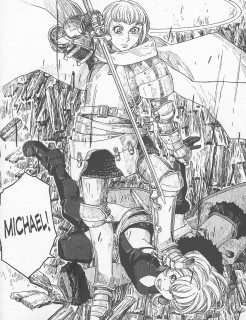

Each of the short manga in Exhibition focuses on a different character of Maria the Virgin Witch: Viv, Maria, Joseph, and Ezekiel. Viv’s story is the only multi-chapter manga in the volume. It follows the English witch from when she first arrived on France’s shores, traveling on a ship filled with soldiers and other witches sent to reinforce England’ armies in the Hundred Years War. This is long before she befriends Maria, but Viv’s enthusiastic and reckless approach to battle, in addition to wreaking havoc, becomes a source of inspiration for Maria’s own efforts. The next story is just as much about Maria’s familiars as it is about Maria herself, taking place during the main series and showing a typical day away from the battlefield after Ezekiel joins their small group. Josephs’ story, like Viv’s, is a prequel to Maria the Virgin Witch, recounting Joseph and Maria’s first adorably awkward meeting as he seeks her aid for France’s war efforts. The volume ends with a story about Ezekiel, not as an angel, but as the human child of Maria and Joseph, providing a nice epilogue for the series as a whole.

The stories in Exhibition are obviously intended for readers who are already familiar with Maria the Virgin Witch and who have already read the entire series. Although the short manga in Exhibition aren’t necessarily directly connected to the main narrative of Maria the Virgin Witch, by their very nature there are some spoilers involved and the collection relies on the reader having previous knowledge of the series’ characters. Exhibition is less devoted to expanding the world and plot of Maria the Virgin Witch and more focused on further developing the manga’s characters and their personal stories. And by telling the stories of the individual characters in Exhibition, more about Maria herself is revealed. Even when she isn’t immediately involved or present, Maria plays an important role in all of the short manga. Exhibition shows many of her different sides: Maria the friend, Maria the master, Maria the lover, Maria the mother, and so on.

The stories in Exhibition are obviously intended for readers who are already familiar with Maria the Virgin Witch and who have already read the entire series. Although the short manga in Exhibition aren’t necessarily directly connected to the main narrative of Maria the Virgin Witch, by their very nature there are some spoilers involved and the collection relies on the reader having previous knowledge of the series’ characters. Exhibition is less devoted to expanding the world and plot of Maria the Virgin Witch and more focused on further developing the manga’s characters and their personal stories. And by telling the stories of the individual characters in Exhibition, more about Maria herself is revealed. Even when she isn’t immediately involved or present, Maria plays an important role in all of the short manga. Exhibition shows many of her different sides: Maria the friend, Maria the master, Maria the lover, Maria the mother, and so on.

Whereas the main Maria the Virgin Witch series had a rather serious story that was accompanied and punctuated with humor, overall Exhibition consistently tends to be much more lighthearted and comedic in nature. It’s a fun collection for fans of the series even if the stories are generally fairly inconsequential. None of the hard questions raised by the main series or the lingering plot threads are really addressed. Maria’s lineage and backstory still remain obscure. (If anything, I’m left wondering even more about her origins and who she really is.) Not much in the way of additional worldbulding is present in the volume either. Instead, Exhibition offers readers the opportunity to enjoy a collection of stories that are charming, funny, and even a little touching as they celebrate the characters of Maria the Virgin Witch. And because the characters are such a large part of what makes Maria the Virgin Witch so appealing, Exhibition is a perfect send-off for the series.