Gengoroh Tagame is an extraordinarily important creator of gay erotic art and manga. He is extremely influential in Japan, but his talent is also recognized worldwide. Tagame’s work has been published in French, Spanish, and Italian, but it wasn’t until 2012 that any of his manga received an English-language release when “Standing Ovations” was collected in the third issue of the erotic comics zine Thickness.

Gengoroh Tagame is an extraordinarily important creator of gay erotic art and manga. He is extremely influential in Japan, but his talent is also recognized worldwide. Tagame’s work has been published in French, Spanish, and Italian, but it wasn’t until 2012 that any of his manga received an English-language release when “Standing Ovations” was collected in the third issue of the erotic comics zine Thickness.

There was a persistent rumor that Tagame didn’t want his work to be published in English, which may have been one of the reasons it took so long for a major release of Tagame’s manga to emerge. Happily, that rumor was unfounded and not at all true; 2013 saw the publication of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame: The Master of Gay Erotic Manga, which collected stories from over a decade of Tagame’s output.

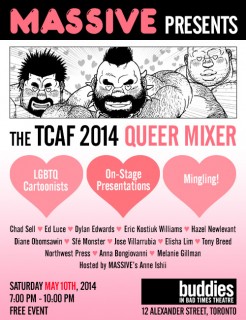

In part, The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame and the efforts of its editor Graham Kolbeins and its producer and translator Anne Ishii led to the establishment of Massive, a line of apparel and goods inspired by gay manga (and especially by the work of Tagame and Jiraiya). Massive also imports, produces, and translates gay manga and collaborates directly with creators of gay Japanese art and comics. I’m very much looking forward to Massive and Fantagraphics’ release of Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make It in late 2014 which will include interviews, photography, essays, illustrations, and manga. Tagame will be one of the nine artists featured in the volume.

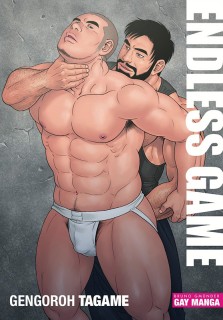

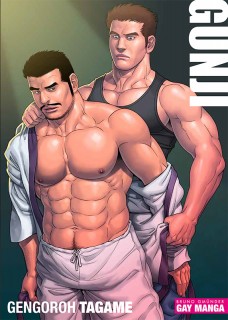

The publication of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame may have also helped to open the doors for the German publisher Bruno Gmünder to release two more collections of Tagame’s work in English: Endless Game and Gunji. Bruno Gmünder specializes in high quality releases of gay fiction, nonfiction, comics, art, and photography, so Tagame’s manga fits the publishing house perfectly. In addition to the manga themselves, the volumes also include color illustrations by Tagame. Endless Game and Gunji are the first volumes in Bruno Gmünder’s Gay Manga line of comics. 2014 will also see the release and English debuts of works by Takeshi Matsu and Mentaiko Itto, as well as one of Tagame’s most recent manga, Fisherman’s Lodge. Tagame was also included in Bruno Gmünder’s 2014 artbook Raunch.

Interestingly enough, Bruno Gmünder’s release of Endless Game was actually the volume’s world debut. The English-language edition of Endless Game was published in 2013, while the Japanese edition of the manga wasn’t collected until 2014. Endless Game originally began serialization in 2009 and was completed in 2012. I was particularly interested in the volume because prior to its publication I had only had the opportunity to read selections of Tagame’s short manga; all one-hundred-seventy-six pages of Endless Game are devoted to a single story about a young jock named Akira and his descent into prostitution.

Tagame is particularly well-known for the hardcore BDSM themes found in his manga and artwork and he doesn’t shy away from rape scenarios in his work. The sex in Endless Game however, while still being hardcore and exceptionally explicit, is entirely consensual. Granted, Akira might not be aware of the extent to which he is being manipulated. But everything that he does, all of the filthy and degrading acts in which he participates, he does so willingly. Akira has an insatiable sexual appetite and even when he is being taken advantage of, he revels in it. There is still power play and intense sexual scenarios in Endless Game, but the extreme brutality seen in some of the shorter manga collected in The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame is missing, making this volume more approachable as a whole to a wider audience.

Tagame is particularly well-known for the hardcore BDSM themes found in his manga and artwork and he doesn’t shy away from rape scenarios in his work. The sex in Endless Game however, while still being hardcore and exceptionally explicit, is entirely consensual. Granted, Akira might not be aware of the extent to which he is being manipulated. But everything that he does, all of the filthy and degrading acts in which he participates, he does so willingly. Akira has an insatiable sexual appetite and even when he is being taken advantage of, he revels in it. There is still power play and intense sexual scenarios in Endless Game, but the extreme brutality seen in some of the shorter manga collected in The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame is missing, making this volume more approachable as a whole to a wider audience.

Gunji collects two of Tagame’s earlier works: the Gunji tetralogy (“Gunji,” “Scars,” “Flash Rain,” and “Pyre”), which was serialized between 2002 and 2003, as well as a slightly revised version of “The Ballad of Ôeyama” from 2004. Both of those manga had previously been released in Japanese and in French before the English translation was published in 2014. The Gunji series was serialized in the Muscle Man manga magazine. The anthology became a crossover of sorts between boys’ love and gay manga and attracted both female and male readers and creators. Because of this, Tagame deliberately incorporated more boys’ love-esque elements into the story. The men, while still very masculine, have considerably less body hair compared to some of his other works. “Gunji” was initially written as a one-shot story, but proved to be popular enough that Tagame followed it up with a serialized prequel. Whereas sex drove the plot in Endless Game, in the Gunji manga the plot drives the sex. The titular Gunji is a skilled sushi chef who is tormented by the sadistic son of his late master, whom he loved.

“The Ballad of Ôeyama” is a historical period piece set in 10th-century Japan. The short manga was inspired by the military commander Minamoto no Yorimitsu (also known as Raikō) and the legend of the oni Shuten Douji. In the afterword, Tagame notes that “The Ballad of Ôeyama” was also greatly influenced by Osamu Tezuka’s 1969 manga General Onimaru which he enjoyed reading as a child. (Even Tagame is influenced by Tezuka!) Raikō and two of his followers are sent to quell a demon which has been terrorizing the people of Ôeyama but find themselves captured instead. The demon, it turns out, is a shipwrecked foreigner who after being shunned for so long desires human contact and forcibly takes Raikō. Tagame’s reinterpretation of the Shuten Douji myth is spun into a surprisingly romantic tragedy. As with the Gunji tetralogy, while the erotic content is certainly important to “The Ballad of Ôeyama,” the story itself seems to take slightly more precedence in the development of the manga. Granted, Tagame himself would be the first to admit that his work is pornography and he is very candid about that fact. But one of the things that I appreciate the most about Tagame’s manga is that in addition to being gorgeously and viscerally drawn they also have interesting narratives and compelling psychological elements.

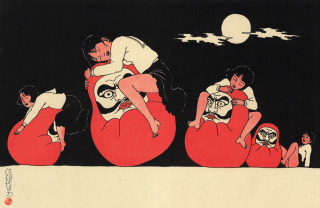

Kaita Murayama, born in 1896, was a Japanese artist, poet, and author. He was best known for his work as an artist, and especially for the originality and vibrancy of his paintings. Although some of his writings were printed while he was alive, most of Murayama’s poetry and prose was collected and published by his friends after his death in 1919 of tuberculosis. Very little has actually be written about Murayama in English. Likewise, very little of his work has been translated. This is unfortunate because both Murayama and his writings are fascinating.

Kaita Murayama, born in 1896, was a Japanese artist, poet, and author. He was best known for his work as an artist, and especially for the originality and vibrancy of his paintings. Although some of his writings were printed while he was alive, most of Murayama’s poetry and prose was collected and published by his friends after his death in 1919 of tuberculosis. Very little has actually be written about Murayama in English. Likewise, very little of his work has been translated. This is unfortunate because both Murayama and his writings are fascinating.