Author: Tetsu Kariya

Author: Tetsu Kariya

Illustrator: Akira Hanasaki

U.S. publisher: Viz Media

ISBN: 9781421521435

Released: September 2009

Original release: 2006

Awards: Shogakukan Manga Award

When it comes to food manga, the long-running and sometimes controversial Oishinbo is one of the most successful series in Japan. Written by Tetsu Kariya and illustrated by Akira Hanasaki, the popular Oishinbo is well over a hundred volumes long and earned its creators a Shogakukan Manga Award in 1987. I don’t expect Oishinbo to ever be released in English in its entirety, but Viz Media did license seven volumes of Oishinbo, A la Carte–thematic collections of stories selected from throughout the series. Oishinbo, A la Carte: Vegetables is technically the nineteenth A la Carte volume, published in Japan in 2006, but in 2009 it became the fifth collection to be released in English under Viz Media’s Signature imprint. If I recall correctly, Oishinbo, A la Carte: Japanese Cuisine was the very first food manga that I ever read. Since then, I have enjoyed slowly making my way through the other A la Carte collections available in English, and so was looking forward to a serving of Vegetables.

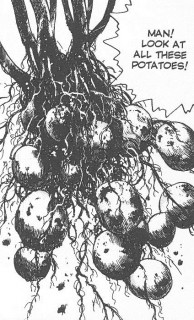

While Vegetables collects Oishinbo stories from different points the series, it also includes some of the earliest arcs. One of the primary, ongoing plotlines of the manga is the competition between Yamaoka, a newspaper journalist heading the “Ultimate Menu” project, and his estranged father Kaibara, who is developing the “Supreme Menu” for a rival paper. The three-part “Vegetable Showdown!” that opens the volume is only their second official battle for culinary dominance. Appropriately for a volume about vegetables (since getting kids to eat them is apparently a worldwide struggle), many of the stories feature children discovering that produce like eggplants, bean sprouts, and carrots might not be so bad after all. At least when they’re prepared well. Adults preconceived notions are challenged in the manga as well, not just about how vegetables are prepared and taste but also about how they are grown and produced. The stories in Vegetables often follow produce from the field to the table.

Oishinbo frequently delves into the politics of food and the series’ characters (and I would assume by extension its creators) have very strong opinions about the matter. Vegetables joins the previous two A la Carte collections in English–Fish, Sushi & Sashimi and Ramen & Gyōza–in particularly stressing the importance of quality ingredients and in arguing very strongly for food that has been safely, responsibly, sustainably, and often locally produced. So far, however, Vegetables seems to be the volume that is most blatant in its activism, villainizing the use of herbicides and pesticides. Opposing viewpoints are briefly entertained, but it is very clear which side of the debate Oishinbo supports. The environmentalist message in Vegetables can be very heavy-handed. Organic produce is often ideal for a number of the reason explained in Vegetables, but the reality is perhaps much more complicated and nuanced than the manga might lead readers to believe.

Oishinbo frequently delves into the politics of food and the series’ characters (and I would assume by extension its creators) have very strong opinions about the matter. Vegetables joins the previous two A la Carte collections in English–Fish, Sushi & Sashimi and Ramen & Gyōza–in particularly stressing the importance of quality ingredients and in arguing very strongly for food that has been safely, responsibly, sustainably, and often locally produced. So far, however, Vegetables seems to be the volume that is most blatant in its activism, villainizing the use of herbicides and pesticides. Opposing viewpoints are briefly entertained, but it is very clear which side of the debate Oishinbo supports. The environmentalist message in Vegetables can be very heavy-handed. Organic produce is often ideal for a number of the reason explained in Vegetables, but the reality is perhaps much more complicated and nuanced than the manga might lead readers to believe.

Overall, I think that Vegetables may actually be one of the weaker A la Carte volumes to have been released in English, but I still enjoyed it. Oishinbo is a series that is educational as well as entertaining and Vegetables is no exception. Although not particularly subtle about its politics, the manga is informative, the individual stories exploring different aspects of produce from how they are grown to what a chef should keep in mind when preparing them. When it comes to vegetables, Oishinbo would seem to argue for simplicity. Produce grown in ideal conditions and in their native environments require very little to enhance their natural goodness and flavor. A dish may be refined, but if the ingredients are of high quality to begin with it does not need to be overly complex. Sometimes only a bit of salt is all that is called for. Food is a major source of the drama in Oishinbo and is often what drives the manga’s plot. And even when it’s not, food–and in this particular volume vegetables–always plays a significant supporting role.